View PDF - Cincinnati History Library and Archives

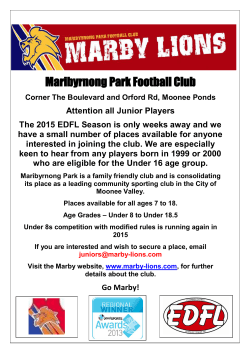

BOSTON. Published by OLIVER DITSON & C0. 451 Washington St. NEW YORK C.H.DITSON & CO. CHICAGO LYON&HEALY. CINCINNATI DOB MEYER & N E W H A L L . SAN FRANCISCO McCURRIE.WEBER & CO. PHILA. J . E.DITSON & CO. 1869 sheet music dedicated to the ladies of Cincinnati The Team that Couldn't Be Beat: The Red Stockings of 1869 by Joseph S. Stern, Jr. W hen the umpire's traditional cry of "play ball" opens the 1969 season at Crosley Field, it will mark the one hundredth anniversary of the nation's first professional baseball team: the Cincinnati Reds, successors to the remarkable Red Stockings. Never in the history of the game has there been another season like that first one for the Red Stockings. In 1869, their initial year as a professional team, they took on all comers, semi-professional and amateur, from coast to coast, emerging undefeated in every one of their sixty-nine games. This incredible record focused national attention on the emerging spectator sport of professional baseball, and bestowed fame on the Red Stockings as well as on their hometown of Cincinnati. When the Red Stockings finally lost their first game (on a fluke play) in 1870, the tension that had steadily built up over two years of undefeated competition was justifiably relieved. But with this first defeat the heart also went out of the ball club. The holy crusade was over; something had snapped; the team actually disbanded at the end of the 1870 season. But it left professional baseball firmly established on the national scene—and this, rather than its extraordinary debut, was the most significant contribution of the immortal Red Stockings. Baseball, with its familiar diamond-shaped infield, developed in America in the 1830's as an outgrowth of the English game of rounders or town-ball. It was an amateur game for gentlemen with time on their hands. Though Thomas Jefferson demeaned games played with a ball as not being so useful as recreation with horses or guns, baseball developed rapidly. Prominent families enjoyed it, and gentlemen's baseball clubs were arranged informally to promote the sport. It soon became apparent that the game was not only enjoyable but, along with cock-fighting, animal-baiting, boat racing and boxing, a good spectator sport as well. From informal club "pick-up" games it was an easy step to organized teams. The Knickerbocker Club of New York, begun in 1845, is generally credited with fielding the first of these. 25 The "Knicks" laid down rudimentary rules that with a little imagination would be recognized by the modern fan. The pitcher tossed underhand from a spot forty-five feet from home plate (overhand pitching didn't begin until 1884). The catcher stood directly behind the batter only when the runners were on base. Originally it took nine balls to earn a walk, and the batter got two chances for a called third strike. The home team chose which half it wanted to bat. The ball itself was similar to today's. The players wore uniforms of blue wool trousers, white flannel shirts and straw hats, and they played barehanded. Then as now, there was an umpire, but he was chosen from among a group of prominent citizens esteemed for fair play. Perched on a stool between first base and home plate, this official cut a dignified figure in his Prince Albert coat, silk hat, and cane. The players likewise were gentlemen of leisure who supposedly played the game simply for the sport. As competition grew keener, however, club members found they really wanted to win. They began to invite would-be gentlemen with particular baseball ability to join their rosters. One of these, who was to figure prominently in the annals of the Red Stockings, was Harry Wright. A young Englishman of working class background, he played cricket with the St. George Cricket Club of Brooklyn, and also was an excellent baseball player. Wright joined the Knickerbockers as a gentleman jeweller's apprentice. He was an amateur in name only, being paid "under the table" for his services. Before long dozens of Harry Wrights were being asked to join clubs; if a team wanted to win, the unwritten rule of "gentlemen only" was out. By 1859, the New York area alone boasted twenty-five or more baseball clubs. On March 9 of that year, the clubs met at Cooper Institute in New York City to establish rules and regulations for an over-all amateur body—The National Association of Baseball Players. This association of individual players served as the nucleus of organized baseball. During the Civil War organized baseball was suspended, but the game was tremendously popular among the soldiers. On Christmas Day, 1862, two "picked nines" of Union Army soldiers played before an estimated 40,000 of their comrades at Hilton Head, South Carolina, possibly the largest crowd in the nineteenth century to witness a sporting event. President Lincoln liked baseball and often took his son Tad out to the ball game, to watch local army teams near Washington. It was during the Civil War that baseball began to be referred to as the National Game. A contemporary Currier and Ives print depicting a baseball scene was titled "The American National Game of Baseball." After the war baseball began to come into its own; the days of the strictly amateur game for "gentlemen only" were waning. With more leisure time for all, blue collar workers wanted to play too, and these men, often being hungrier, played to win. Local pride naturally made for intense rivalries. Originally clubs played only against neighboring teams, but from these games 26 would emerge the best team, which soon was playing its counterpart in another city. With better performances, clubs began to charge admission. As early as 1864, the New York Mutuals charged ten cents admission when they played the Brooklyn Atlantics. The smell of commercialism was in the air. As good players won greater recognition, clubs began bidding for their services. At first, sub rosa offers were made, in the form of shares of the gate receipts and bribes from gamblers. The best players were quick to take advantage of this bull market. Al Reach, who later started the famous A. J. Reach Sporting Goods Company and was a star infielder for the Philadelphia Athletics, took a straight salary in 1863. Reach's success, and that of others like him, made such a sham of amateurism that the National Association of Baseball Players declared amateurs should be separated from professionals, and defined a professional as one who plays for money. The lure of good pay soon made professional ball playing a coveted career; young working class men saw an opportunity for fame and fortune. In 1868, the Brooklyn Atlantics were a typically motley team: their pitcher was a stone mason, the catcher a postal employee, one of the infielders a shipping clerk, another a glass blower. Soon the teams became mixed, part professional, part amateur, but some clubs tried hard to preserve their original intent by developing second teams, strictly gentlemen amateurs. These were derisively referred to as "muffins" (like "duffers" in golf) by the pros who were attracting the spectators. Still, there were, as yet, no all-professional teams. In 1868, the New York Clipper, SL popular theatrical newspaper which also covered sports such as boxing, crew racing, sculling, cock fighting, billiards, rackets, the turf, the trigger (pigeon shooting), chess, aquatics, sailing, bullfighting, and snowshoe racing, began to take baseball seriously. In an effort to dignify as well as publicize the game, its editor, Frank Queen, offered a gold ball to the nation's championship team and individual medals to the outstanding players at each position. The Clipper was the sole arbiter of who was best, and Queen became to early day baseball what Walter Camp became to football when he created the "All American" awards. The Clipper awards were highly coveted and immediately lent prestige to the game. The June 8, 1868, Clipper boasted: The Clipper, as the leading organ of all legitimate sports, was the first to recognize in the game of baseball a recreation that was destined to be the National Game of America. . . . With the sole desire to foster a spirit of emulation among clubs and players we offer these prizes. It matters not to us who wins in our noble game. We know no North, no South, no East, no West. . . . Although the East has heretofore been the great baseball playground of the country, the West is making rapid strides and bids fair to outstrip the East. 27 Henry Chadwick, a writer for the Clipper and a baseball enthusiast, became the game's greatest publicist. He could describe a game in a wonderfully exciting manner, but he was disturbed by the inconsistent status of the team players themselves. While championing all-professional teams, he publicly denounced the so-called amateurs who accepted fees or who became "revolvers" (players who left their club in the lurch if they had a better offer from another club ). In previewing the coming 1868 season, Chadwick let it be known which teams he considered best. They included the Brooklyn Atlantics, the New York Mutuals, the Troy Haymakers, the Chicago White Stockings, the Philadelphia Athletics, the Baltimore Marylands, and the newly-formed Red Stockings of Cincinnati, an obscure but up-and-coming club with a unique characteristic. Each member of the Cincinnati team, he noted, was under contract to play for the whole season as a professional player at a negotiated rate of pay. With that announcement, Chadwick became the fledgling Red Stockings' biggest booster even though he himself was a New Yorker—for now he had his all-professional team. The Cincinnati Baseball Club, which sired the Red Stockings, was organized July 23, 1866, in the law office of Tilden, Sherman, and Moulton, in the old Selves Building at 17V& West Third Street. Alfred T. Goshorn, an early Cincinnati "wheeler-dealer" (who later became Sir Alfred, the only American up until then ever to receive a title, when knighted by Queen Victoria for his work at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition) was elected president; Aaron B. Champion, vice president; Henry Glassford, treasurer; George Ellard, manager; and William Worthington, first scorer. The Cincinnati Baseball Club was an amateur group made up mostly of young attorneys, many of whom were Harvard and Yale graduates of the late 1850's and early 1860's. They had been attracted to the sport in college, and some of them would get up at four in the morning, don baseball outfits, and go down to play a game before breakfast. On reaching the grounds at the foot of Ninth Street in the Millcreek bottoms, not far from present day Crosley Field, they would choose up into two teams—the Morning Glories and the Wide Awakes. After a game, they would return home, eat breakfast, dress in street clothes, and go about their business. The club in 1867 had 380 members. Some of the well-known names in Cincinnati at that time were on its roster, among them Bellamy Storer, Jr., John R. McLean, George W. Neff, Larz Anderson, Samuel Kemper, Drausin Wulsin, Quinton Corwine, Stanley Matthews, Nicholas Longworth II, J. William Johnson, Andrew Hickenlooper, A. Howard Hinkle, Murat Halstead, Rufus King, Jr., James N. Gamble, William Procter, Joseph S. Peebles, C. M. Erkenbrecher, John L. Stettinius and Asa Woodmansee. The influence of baseball was now felt keenly in the city, and new clubs were forming all around town. Almost every suburb, from Riverside to Walnut 28 The popularity of amateur baseball during the 1860's encouraged Alfred T. Goshorn, right, and Aaron B. Champion, below, to field the nation's first all-professional team —the Red Stockings. Hills, had a team of amateur players. Young William Howard Taft played with the Mount Auburn nine, along with Stewart Shillito, who ran a dry goods store. The Avondale Club had William Greenwood, while Charles Resor and William McAlpin played for Clifton. In early 1867, the club relocated on the grounds of the nearby Union Cricket Club, then eleven years old. These grounds were used for cricket and baseball in the summer and were flooded for skating in the winter. George Ellard, a baseball enthusiast who owned a sporting goods store, was president; Harry Wright was listed as property man. He was the same Harry Wright of the St. George Cricket Club of Brooklyn, who had been imported the year before to man the position of bowler for the Union Cricket Club. In June 1867, the U.C.C. and the Cincinnati Baseball Club merged, with the latter's name surviving. It was decided to build a clubhouse on Freeman Avenue, fence in the grounds, and charge twenty-five cents admission either in coin or in paper "shinplasters" for all matches. George Ellard designed uniforms for the players: white flannel shirts, caps, and knee-length trousers, with distinctive long red stockings. It was from these handsome red stockings that the team promptly derived its nickname. The principal local rivals of the Cincinnati Baseball Club in 1867 were the Buckeyes and the Live Oaks. The Buckeyes, in fact, were the first organized baseball team in Cincinnati, having been formally chartered in 1863, with grounds in the old Millcreek bottoms. The mayor of Cincinnati, Charles F. Wilstach, was an honored member of the Buckeyes. As the rivalry developed, the Red Stockings brought in more ringers, in addition to Harry Wright, to form the first nine, causing much discord in the club. Many of the strictly amateurs, men like Henry Probasco, Miller Outcalt, and Joseph Griffith, felt that importing players from other cities would kill baseball, so they formed a second team which called itself the Cincinnati Amateurs. The 1868 Red Stockings were still about half amateur and half professional, Rufus King, Bellamy Storer, and J. William Johnson being the most prominent of the amateurs. The first team was so good that three of its members, J. V. Hatfield, the left fielder, Fred Waterman, the third baseman, and Johnson, the right fielder, were awarded the coveted Clipper medals, each being judged best in the country in his position. Of these, only Johnson, a well-known and popular attorney, was a real amateur. The Clipper awards were presented in November after the close of the 1868 season and lent great prestige to the emerging Red Stockings. The rival Buckeyes, who also had a few pros but none of whose players received so much as an honorable mention, were infuriated. This led to dissension in the club and in April 1869 just before the start of the new season the old "Bucks" were dissolved. Not only the Bucks were unhappy, though; J. William Johnson himself thought the game was becoming a travesty. "All amateur or all professional," he asserted, "you can't mix the two." In defense of his 30 position, he resigned from the Red Stockings. He concurred with the Clipper's Henry Chadwick, who staunchly propounded the thesis that baseball should emerge as a commercial spectacle, offering the players a true profession. A group of baseball clubs in the East gave lip service to this proposition, but after Johnson's resignation the key members of the Cincinnati Baseball Club, Goshorn, Champion, and Ellard, decided to do something about it. In a determined fashion, they went about putting together an all-professional team, hiring the best players they could get from wherever they could get them. They already had a sound nucleus and a superb player-captain in Harry Wright. During the winter of 1868, Harry persuaded his brother George to come out to Cincinnati from Washington and the ball was rolling. As George Ellard, who has been called the father of professional baseball, described it: "When the Cincinnatis stepped upon the diamond in 1869, they were the first regular professional nine ever gotten up in the country." For the first time in history, the actual salaries paid for the March 15-November 15 season were published in the newspaper. The 1869 Red Stockings' roster and salaries as published in the Clipper were as follows:1 Harry Wright, Captain George Wright Asa Brainard Fred A. Waterman Charles J. Sweasy Charles H. Gould Douglas Allison Andrew J. Leonard Calvin McVey Richard Hurley Center Field Shortstop Pitcher Third Base Second Base First Base Catcher Left Field Right Field Substitute New York Washington New York New York Newark Cincinnati Jersey City Newark Indianapolis Indianapolis $1,200 $1,400 $1,100 $1,000 800 800 800 800 800 800 In his book Baseball in Cincinnati, Harry Ellard, George's son, described the players in a style that is not unfamiliar today. Douglas Allison was an unequalled cool and steady player whose "chief merit as a catcher lay in a manner in which he handled foul tips, the most dangerous kind of batted balls then, . . . no matter how hot they came." Asa Brainard, the pitcher, "delivered a swift, twisting sort of a ball. . . [and] very rarely pitched a ball where the batsman expected it. . . ." Charles Gould, the only native Cincinnati man on the nine, was familiarly known as "the bushel basket" because no ball that came toward him ever got by. George Wright, as shortstop, "covered more ground in his position than any other man in the country. . . . He was active as a cat, and the way he pounced on a hot daisy-cutter [grounder] and picked it up, or made a runningflycatch, was wonderful."2 Harry Wright was described as "the best captain in the world. . . . He was always quiet and self-sustained in his demeanor, but he gave his orders with decision, and these were always obeyed implicity. In correcting any mistake of his men, he never did it in an offensive or arbitrary manner. His favorite expression, 'You need a little more ginger,' acted as effectively as stronger language. . . . He never got discouraged . . . and by his conduct always inspired his men with confidence in their ability to win."3 At a meeting of the Cincinnati Baseball Club on April 5, Alfred Goshorn resigned as president so that Aaron Champion, now the driving force, could take his place. Champion, a bright and able young lawyer from Columbus, Ohio, who moved to Cincinnati in 1864, became interested in baseball as a stimulus to local business. Earlier, he had successfully organized the Union Cricket Club, and in 1868 raised $11,000 to refit the Union Grounds as the Red Stockings' home field. He sold $13,000 worth of stock in the Cincinnati Baseball Club to members in order to secure players. He would have liked to sign up all the Clipper gold medal winners of 1868, which would have been the equivalent of buying the National League All-Star team today. He did not, of course, and the Clipper admonished him for his attempt, but, undaunted, Champion assembled the remarkable team just described. Even before the season started, team spirit was high. The players reported themselves to be in good shape, and Champion, sensing that he had a winning club, decided to make an eastern tour challenging all comers for the championship of the country. Champion also realized the value of good publicity and arranged to have Harry M. Millar of the Cincinnati Commercial appointed full-time reporter for the team, accompanying it wherever it went. Later, Millar and Henry Chadwick formed an embryonic Baseball Writers Association. The 1869 baseball season started off modestly enough. There were no Opening Day ceremonies for which Cincinnati was later to become prominent, no brass bands, no important officials throwing out the first ball. On April 17 at the Union Grounds, the Red Stockings won 24 to 15 over a team composed of the best local players. By late May the team seemed ready for its challenging eastern tour. The night before their departure by train from Cincinnati, President Champion visited each player in his room at the Gibson House to be sure of his whereabouts. He knew the coming trip was going to be hazardous and that gate receipts depended on the players being in first rate condition. Harry Wright vouched for his men; they in turn respected their modest captain. By June 12, the Red Stockings had defeated seventeen teams, including the Harvard College varsity nine by a 30 to 11 score. They were scheduled to play Yale on June 14 in New Haven, Connecticut, but were rained out and moved on to New York, fresh and in fit condition for their much-heralded game with the Mutuals the following day. The New York Mutuals were considered the best team in the country and the pre-season choice for national honors. They had already defeated the Atlantics of Brooklyn, another pre-season favorite, 32 , >» • • The Clipper medals for outstanding play created popular support for the 1869 Cincinnati team, which played on a diamond differing only slightly from today's. and the fast-charging Athletics of Philadelphia. But the undefeated Red Stockings were coming into town and excitement was running high. There was a great deal of betting, and by game time 7,000 fans had gathered while a thousand more perched on housetops overlooking the Union Grounds in Brooklyn where the game was to be played. The game was well covered by the press. The Cincinnati Gazette headlined it: VICTORY NO. I I FOR THE BOYS THE TOLERATED CHAMPIONS MEET A WATERLOO CLOSEST FIGHT AND SMALLEST SCORE ON RECORD We are tossing our hats tonight, and shaking each other by the hand. We are the lions, and baseball men are looking curiously at us as the club over whose grounds, it is possible, will soon float the whip pennantemblem of the national championship. . . . All this, because we have beaten the Mutuals, and because the game was the toughest, closest, most brilliant, most exciting in baseball annals. When the Mutuals had finished their ninth inning, and the Cincinnatis went to the bat, the score standing even—two to two—the excitement of the great crowd was intense beyond descripion. Every motion, every movement, every thought it almost seemed, of the players was watched as drowning men watch the progress of a rescuing boat. When Leonard went out with no runs secured, the excitement became almost fierce. But a moment or two after in came Brainard with an immense rush and a bound, and the great game was won. . . . The score stood 4 to 2. . . . The Mutual ball was given us, and we had beaten the big club.4 Harry Ellard described the scene in Cincinnati: When the news of the victory at Brooklyn reached Cincinnati the excitement was beyond description. Salutes were fired, red lights burned and cheers were deafening. Everybody felt in the finest spirits, and many were willing to lend their friends, and even their enemies, any sum without question. Bands were playing all over town and joy reigned supreme.5 After this celebrated game with the Mutuals, the Red Stockings walloped the Brooklyn Atlantics 32 to 10. They moved on to Philadelphia where they beat the Athletics, then to Washington, D.C., where they defeated the Nationals. President Grant himself viewed the game and later complimented the players on their performances. On July 1 the team came home from its enormously successful eastern tour with an unblemished record. The players, as could be expected, were given a royal reception. The Cin34 cinnati Lumber Company presented the team with a huge bat twenty-seven feet long. On its side was painted "Champion Bat," and underneath was inscribed each player's name. That evening there was a grand banquet at the Gibson House attended by many local notables who proposed appropriate toasts. When Aaron Champion was called upon he caught the spirit of the occasion by remarking, "Some one asked me today whom I would rather be, President Grant or President Champion of the Cincinnati Baseball Club. I immediately answered him that I would by far rather be president of the baseball club."6 But the season was only half over. On July 24, the Red Stockings narrowly defeated the spunky Forest City Club of Rockford, Illinois, 15 to 14. Forest City had the services of its great young pitcher A. G. Spalding, who later became the famous sportings goods manufacturer. On August 27, the Haymakers of Troy, New York, were in Cincinnati to avenge an early season defeat, resulting in the most controversial game of the season. The Haymakers were one of Chadwick's pre-season favorites, and unusual interest was attached to the game because it was rumored that team owner John Morrissey, an upstate New York politician and friend of Boss Tweed, had wagered $17,000 on his club.7 The visitors took an early lead but by the end of the fifth inning the score was 17 to 17, and it was obvious that the Red Stockings were coming on fast. In the sixth inning, Morrissey, in order to avoid paying off his bet, contrived to have the Haymakers leave the field. A near riot ensued, and even though the umpire gave the game to the Red Stockings, it went into the record books as a tie. Enraged at the proceedings, Champion called a special meeting of the Cincinnati Baseball Club to discuss the matter. The Haymakers' portion of the gate receipts was withheld; it was not until some months later when a rightful apology was made that they received their share. The affair was, of course, scandalous, and jeopardized the future of baseball. On August 28, the Cincinnati Gazette editorialized: The game of baseball has become a national institution [and] for the most part . . . has been free from the objectionable features which commonly attach to outdoor sports. Bets have, of course, been made upon the issue of match games. But these have been privately made, and the players themselves have, as a rule, we believe, been free from the reproach of using their profession as a means of gambling. This has been notably the case with the Cincinnati Baseball Club. It was organized and is conducted by gentlemen who are incapable of using the club for the purpose of making money, and no suspicion has ever fallen upon the Red Stockings of ever having resorted to any tricks to win or save money, staked upon their success. Unfortunately, they came in collision last Thursday with a club whose 35 In July 1869, following the successful eastern tour, Cincinnati wined, dined and presented her team with a twenty-seven foot "champion bat." Scores Made by the Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869 April May June 17 24 4 10 15 22 29 1 2 3 4 7 8 9 10 11 12 15 16 Red Stockings Picked Nine, Cincinnati 24 Picked Nine, Cincinnati 50 Great Western, Cincinnati 45 Kekionga, Fort Wayne, Ind 86 Antioch, Yellow Springs, 0 41 Kekionga, Fort Wayne, Ind 41 Great Western, Mansfield, O. (3 innings) . 35 Independents, Mansfield, 0 48 Forest City, Cleveland 25 Niagara, Buffalo 42 Alerts, Rochester 18 Haymakers, Troy, N. Y 37 Nationals, Albany 49 Mutuals, Springfield, Mass 80 Lowell, Boston 29 Tri-Mountain, Boston 40 Harvards, Boston 30 Mutuals, New York 4 Atlantics, New York 32 Opponents 15 7 9 8 7 7 5 14 6 6 9 31 8 5 9 12 11 2 10 17 18 19 21 22 24 25 28 30 July 1 3 5 10 13 22 24 28 30 31 August 2 4 5 6 11 16 23 27 31 September 9 10 15 16 26 27 29 30 October 1 11 12 13 15 18 22 24 November 4 5 Red Stockings Eckfords, Brooklyn 24 Irvingtons, New Jersey 20 Olympics, Philadelphia 22 Athletics, Philadelphia 27 Keystones, Philadelphia 45 Marylands, Baltimore 47 Nationals, Washington, D.C 24 Olympics, Washington, D.C 16 Baltics, Wheeling, W. Va. (3 innings) . . . . 44 Picked Nine, Cincinnati 53 Olympics, Washington, D.C. 25 Olympics, Washington, D.C 32 Forest City, Rockford, 111 34 Olympics, Washington, D.C. (7 innings) .. 19 Buckeyes, Cincinnati (5 innings) 71 15 Forest City, Rockford, 111. (4 innings) Empires, St. Louis 15 Cream City, Milwaukee 85 Forest City, Rockford, 111 53 28 Forest City, Rockford, 111 Central City, Syracuse 37 Central City, Syracuse (8 innings) 36 Forest City, Cleveland 43 Riversides, Portsmouth, 0 40 Eckfords, Brooklyn 45 Southern, New Orleans 35 Haymakers, Troy, N. Y. (5 innings) 17 Buckeyes, Cincinnati 103 Olympics, Pittsburgh 54 Alerts, Rochester 32 Unions, St. Louis 70 Empires, St. Louis 31 Eagles, San Francisco 35 Eagles, San Francisco 58 Pacifies, San Francisco 66 Pacifies, San Francisco 54 Atlantics, San Francisco (5 innings) 76 Omahas, Omaha (7 innings) 65 Otoes, Omaha (5 innings) 56 Occidentals, Quincy, 111 51 Marions, Marion, Ind 63 Athletics, Philadelphia 17 Louisville, Louisville 59 Cedar Hill, Cedar Hill, 0 40 Eagles, Covington, Ky. (6 innings) 40 Mutuals, New York 17 37 Opponents 5 4 11 18 30 7 8 5 0 11 14 10 13 7 15 14 0 7 32 7 9 22 27 0 18 3 17 8 2 19 9 9 4 4 4 5 5 1 3 7 4 12 8 10 10 8 reputation has not been unimpeached, and which so conducted itself here as to confirm the suspicion that it was the tool of speculators. Their conduct was a disgrace to themselves, a disgrace to the game, and an insult to the Cincinnati club and the audience who had received them with every courtesy, and treated them with strict impartiality. But the circumstance is chiefly to be regretted because its tendency will be to prejudice the minds of the public against the game, and lead them to suppose that baseball, like some other sports, is under the control of the gambling fraternity. We hope that this single instance, the first that has ever occurred in this city, will not lead to such results. Henry Chadwick wrote a similar chastisement in the New York Clipper. He felt that baseball had been dealt a damaging blow, but was optimistic that it would not be permanently crippled.8 Having conquered in the East and at home, the team, still undefeated, again left town on September 14 for a western tour. The western teams were hardly a match for Cincinnati. St. Louis was the first stop, where the Unions went down 70 to 9. The Eagles of San Francisco fell before the Red Stockings on September 26 and 27, as did all the other clubs in the area. And just for variety, Harry Wright led his team to a victory over the Eagles in a game of cricket as well. Stung by earlier defeats, the Philadelphia Athletics and the New York Mutuals then journeyed to the Queen City to challenge the Red Stockings on their home grounds. The exhilarated Cincinnatians climaxed the season by beating the Athletics on October 18 and the Mutuals on November 5. The Mutuals wanted to try again, but enough was enough, and President Champion declined, claiming the Union Grounds were scheduled to be flooded in preparation for winter skating. And there it was: sixty-eight victories, one tie, and no defeats. Thus ended the long season of the most successful baseball club this country has ever produced. The New York Clipper summed it up on November 13: The unprecedented success of the Cincinnati Club is a bright spot in the annals of the game. The triumphant march of the Red Stockings from one end of the country to the other will pass into the history of the national game as the greatest achievement since the healthful and exhilarating pastime was first incepted. And again, the Clipper on December 25, in an editorial "A Little Plain Talk," extolled the virtues of the club in the grandiose verbiage of the day: Now in order to have something as a 'beau ideal' it is necessary to have one club who, by skillful management or superior play, is looked upon as 38 superior and for that purpose we will take the Western Department and choose as our 'beau ideal the Cincinnati Club because it is better managed. It has passed a season without losing a game against the strongest clubs, having journeyed from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, from the Great Lakes to the Capitol, thus traversing more ground than any two clubs in the country. The Red Stockings began the 1870 season with the same players as the year before. The season started out almost a repeat of the previous year. The best local teams were defeated; an eastern tour was arranged; Harvard and Yale again were scheduled, with the Red Stockings trouncing Harvard in Boston on June 4. Their game with Yale the next day was rained out just as it had been the year before, and then on to New York for a game on June 13 with the Mutuals. The Clipper exclaimed, "Where there was one person that knew that the Red Stockings were in New York last year, fifty persons knew it this year." The game wasn't even close, Cincinnati winning 16 to 3. Sports writers began predicting the team would go through another undefeated season, for they had won twenty-seven games so far, ten on the eastern tour. But deep down everyone knew they couldn't go on this way forever. When would the phenomenal winning streak end? Then in New York on June 14, 1870, the Red Stockings met another of their old rivals, the Brooklyn Atlantics. The odds favored the visiting Cincinnati team 7 to 1. In a special dispatch the Cincinnati Gazette reported, "An immense crowd assembled on the Capitoline Grounds this afternoon, to witness the game between the Red Stockings and Atlantics. . . . A few faint cheers greeted our boys as they put in their appearance." At the end of the ninth inning the score was 5 to 5. The Atlantics, who wanted to call the game a draw, carried their bats to the clubhouse. Thousands of spectators left the ground, but Captain Wright insisted the game be played out, and President Champion backed him up. The Red Stockings remained on the field and the umpire, agreeing with Wright, summoned the Atlantics to return. They did and the tenth inning was played out with neither team scoring. In the eleventh inning, the Red Stockings tallied twice and it looked as though their unbeaten record would continue to hold up. With one out for the Atlantics and Smith on third, Start hit a long ball to right field. Then, according to the New York Clipper, As the ball came towards the crowd they gave way, and it fell upon the bank-side almost dead. McVey [the Reds' right fielder] was after it like a flash, but as he stooped to pick up the ball in the crowd one of the partisans present jumped on his back. The crowd did not sympathize with his style of work. . . . but before McVey could handle and throw the ball, Start secured his third, Smith having preceded him home.9 39 Strangely enough, no reporter questioned this bizarre incident. The game continued, as Ferguson sent Start home and made his first base on a safe field grounder. The game now stood a tie, and intense and breathless are no kind of adjectives to express the excitement that prevailed. Zettlein went to his first on a hot liner, well stopped by Gould. Hall hit to G. Wright, who threw to Sweasy. Sweasy muffed it, and then, as Ferguson was already running toward the home plate, he threw to Allison [the Reds' catcher\, who missed it, and Ferguson came in, making the winning run. Then came applause such as I have never heard on any other occasion. It seemed as if the people could not contain themselves. They cheered and swung their hats, and yelled, and shouted, and danced, till it seemed as if they would go wild. The club that had been regarded as the Invincible had been beaten—for the first time in two years.10 President Champion sent the following dispatch home: New York, June 14, 1870—Atlantics, 8; Cincinnatis, 7. The finest game ever played. Our boys did nobly, but fortune was against us. Eleven innings played. Though beaten, not disgraced.!! But with that first defeat something happened to the team. The players had known they couldn't keep winning forever, and expressed relief; but they soon lost again on July 27. This second defeat was followed shortly by the resignations of Aaron Champion as president and John P. Joyce as vice president on August 16. Champion, whose energy and ability had been vital to the Red Stockings' success, and Joyce had both served without any compensation from the beginning. They had accomplished what they set out to do and now felt they must return to their businesses. No one could criticize them, but without them the team collapsed. Wright alone could not hold the players together. Before the end of the season, public interest also waned. The fans were no less fickle a hundred years ago than they are today. The breakdown became complete when Harry Wright, the peerless captain, no longer able to counsel with Champion, announced he would join the Boston Baseball Club the following season. He took with him Gould, George Wright, McVey and Leonard—over half the team. The Cincinnati Baseball Club was forced to disband on November 20, 1870, after the close of the season. A notice went out to members advising them the club could not meet the higher salaries being offered by other clubs. In one brief year all it had left was a glorious memory. Yet the Red Stockings had set a successful pattern—an all-professional team with a regular field manager. Their unprecedented success aroused such enthusiasm for the game that by 40 1871 a score of teams throughout the country had followed their example. The stage was now set for the formation of a baseball league. On March 17, 1871, the National Association of Professional Baseball Clubs was organized with member teams from thirteen cities. But the association was marred from the start by drunkenness, bribery, desertion and breach of contract. In such an atmosphere William "Boss" Tweed, a founding member of the association who owned the New York Mutuals, saw his team flourish while most of the other teams floundered. The one exception was Harry Wright's team from Boston. With the Cincinnati Baseball Club no longer in existence, Wright had expropriated the celebrated Red Stockings' name for his new club—a name which has been associated with Boston ever since. He also signed up A. G. Spalding, the phenomenal young pitcher from Rockford, Illinois. Wright maintained good discipline among the players and won the association championship four times in a row. By 1875, the original thirteen clubs in the association had dwindled to seven; it could not survive long under these conditions and folded that same year. Yet it was a major league, the first one ever, and out of its demise came the formation of the National League. On February 21, 1876, representatives of seven clubs, including John Joyce of Cincinnati, met at the Gait House in Louisville to draw up plans. Joyce represented George and Josiah Keck, who owned a brand new professional Cincinnati Baseball Club. Whereas the old National Association of Professional Baseball Clubs was a loose organization, the new National League put teeth into its charter from its inception. It created a firm schedule and centralized control of a team through the club rather than through the players. The history of the National League is another story, but it couldn't be told without the Reds. There has been a Cincinnati Reds team in it from the beginning, the only one of the original clubs that remains today. And with them is the enduring heritage of the old Red Stockings—the team that couldn't be beat. S. S T E R N , J R . , is President of J. S. Stern, Jr. &• Company and Adjunct Professor of Business Policy at the University of Cincinnati. JOSEPH (1) New York Clipper, June 19,1869. (2) Harry Ellard, Baseball in Cincinnati (Cincinnati, 1907), p. 145-46. (3) Ibid., p. 145. (4) Cincinnati Daily Gazette, June 16, 1869. (5) Ellard, p. 161. (6) Ibid., p. 165. (7) Cincinnati Daily Gazette, August 28, 1869. (8) New York Clipper, August 29, 1869. (9) Ibid., June 14,1870. (10) Cincinnati Daily Gazette, June 15, 1870. (11) Ellard, p. 189.

© Copyright 2025