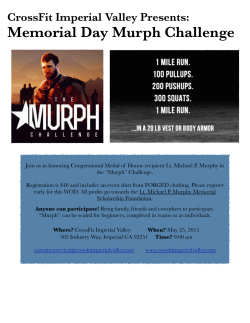

JOURNAL - CrossFit