Seminatural forestry combined with Conservation?

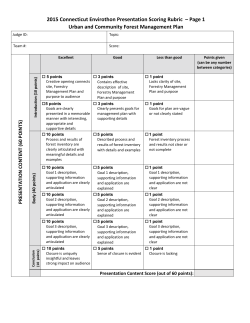

Seminatural forestry combined with Reserves: a success story for biodiversity Conservation? Asko Lõhmus & the Conservation Biology Group, University of Tartu Contents: simple complex Theory Real story Future Theory: combining conservation and forestry toolboxes at landscape scale Biodiversity values Society’s demands • • • • ecosystems species genes goods and services Land allocation e.g. TRIAD approach Seymour & Hunter 1999 Set-asides • • • • area zoning spatial pattern active mgmnt Managed forests Monitoring • • indicators communication • • • • plantations multiple use silvicultural systems silviculture The necessity for broad-scale success stories • to combine historical, socio-economic, and ecological realities • „anachronistic“ approaches prevail Legacy approach European „time-machine“ Angelstam et al. 2011 Forestry. ? „Living“ sustainable reality Planning approach Pacific Northwest restoration plan Franklin & Johnson 2012 J. For.. The case of Estonia Key Facts 49% of land cover Biodiversity: ca. 20,000 species Economy: 4% GDP (8% export; net exporter) State-owned forest: 41%, all FSC-certified Zoning: 10% strictly protected + 15% restricted-management EEA 2014; Statistics Estonia ; Lõhmus et al. 2004 Ecol. Bull. Moderate-input • … seminatural forestry 90% clear-felling origin ditch maintenance 92% nat. regenerated 2% thinned annually no herbicides, fertilizers 84% mixed forest 23% multi-aged 40% wetland drained 60% 31-90 yrs >600 ha wildfire annually 1. Large carnivores (integrity) FOREST RESERVES Populations (hunted): • wolf – 200 (78) • brown bear – 550 (38) • lynx – 400 (16) Genetic barriers detected: • islands only Lynx: 90% quality habitat outside reserves Külvik et al. 2003 Adv. Ecol. Sci.; Hindrikson et al. 2013 PLoS ONE; EEA 2014; R. Kont, M. Keis et al. 2015 / LOORA 2. Polypore fungi (dead wood / manag. intensity) Downed DW (mixed forest) Species richness declines: • 15% with thinning • 9%–22% with artificial regeneration • 1st generation forest thinned No. of polypore species 45 40 R2 = 0.55 35 30 2-ha plots 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 25 50 75 100 125 Logs, m3 / ha 150 175 200 Lõhmus & Kraut 2010 For. Ecol. Manag.; Lõhmus 2011 J. For. Res. + unpubl.; Lõhmus et al. 2013 Eur. J. For. Res.; Sellis 2014 M. Sc. 3. Saproxylic beetles (retention harvest) Critical habitat outside reserves: • most species prefer early-successional sites, notably retention cuts; • substrate seldom limits; no stand-scale thresholds Preferences of 34 modelled species A. Kraut et al. , in prep. 4. Woodpeckers (regeneration retrospective) • long-term increases, supported by tree-species mixtures • protected areas as „back-ups“ – no density differences when accounting for tree composition Three-toed WP White-backed WP Lõhmus et al. , submitted 5. Amphibians (hydrology) Semi-open or sparsely wooded wetland Large undrained reserve Artificial drainage Closed stand Natural habitat Ecological trap Lost habitat Clear-cutting, road building Novel habitat Suislepp et al. 2011 For. Ecol. Manag.; Remm et al. 2015 Boreal Envir. Res.; E. Soomets, unpubl. data • Predation, possibly combined with landscape change Lahemaa NP population – all grouse species • Loss of forest-meadow mosaics and wooded grasslands – Green Woodpecker (Picus viridis) a most abundant woodpecker → small island population remaining Improving retention forestry? E. Aomets Managing predators or their access? E. Kask 6. Long-term declines (specific causes) Conclusions When supported by reserves, biodiversity conservation can be successfully integrated with viable forestry sector. *** Seminatural forestry can sustain many „matrix“ habitats, but intensities (input; expectations) matter much. At best, reserves serve specific goals and provide ‘backup’ habitats, rather than carrying the critical load. Multiple focal taxon groups provide unique guidance in terms of limiting factors and the management success and priorities.

© Copyright 2025