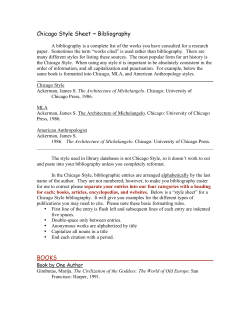

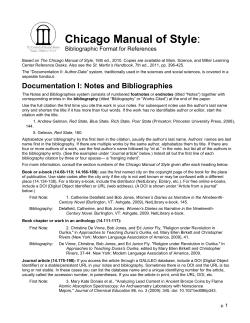

CHICAGO DOCUMENTATION STYLE: BIBLIOGRAPHY PAGE

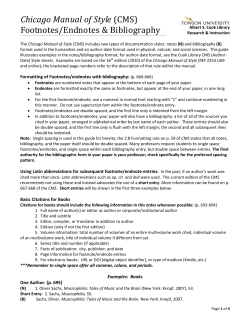

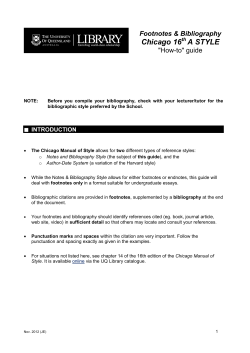

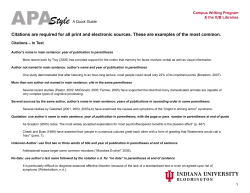

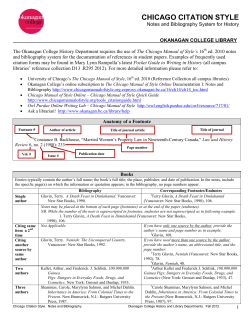

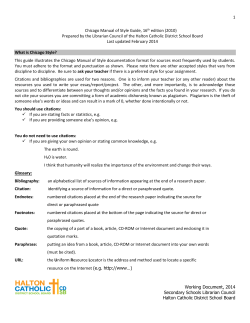

Updated for th 16 edition! CHICAGO DOCUMENTATION STYLE: BIBLIOGRAPHY PAGE Most texts written in History (and some in other humanities disciplines) use Chicago style to cite sources. Chicago-style documents include in-text superscript numbers referring to footnotes or endnotes (see quicktip on “Chicago Documentation Style: Footnotes/Endnotes,” which includes the notes for the sources on this page) along with a more detailed listing of sources in a separate Bibliography page at the end of a document (see sample on back of this page). The requirements for what to include in Bibliography entries are designed so that another researcher could find and refer to the same sources you’ve included. Below are guidelines adapted from Diana Hacker and Nancy Sommers’s A Writer’s Reference, 7th ed., that show the basic principles of some common forms of Chicago Bibliography citation: Book 1 Author(s) 2 Title and subtitle 3 City of publication 4 Publisher 5 Date of publication 1 4 3 Burrows, Edwin G., and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. 5 Work in an anthology 3 2 1 1 Author 2 Title of work 3 Title of anthology 4 Name of editor(s) 5 Page numbers 6 City of publication 7 Publisher 8 Date of publication 2 Pharoah, Sarah. “The Case of Sarah Pharoah.” In Early Native Literacies in New England: A Documentary and Critical Anthology, edited by Kristina Bross and Hilary E. Wyss, 86-87. Amherst: University of 4 Massachusetts Press, 2008. 5 6 7 8 Journal article from a database 1 Author 2 Title of article 3 Title of journal 4 Volume and issue numbers 5 Date of publication 6 Page range 7 DOI, or database name and accession number (AN) 2 1 Souther, J. Mark. “The Disneyfication of New Orleans: The French Quarter as Facade in a Divided City.” Journal of American History 94, no. 3 (2007): 804-11. Academic Search Premier (28142054). 4 3 5 6 7 Short work from a website (include as many of these items as are available) 1 1 Author 2 Title of short work 3 Title of site 4 Sponsor of site 5 Publication or modified date, or date of access if no pub. date avail. 6 URL 2 3 Whitman, Walt. “Remembrance of Erastus Haskell.” Civil War Treasures from the New-York Historical Society. Library of Congress. Accessed July 3, 2012. http://memory.loc.gov/ndlpcoop/nhnycw/al/ 4 5 6 al00/al00004/001v.jpg. Here is an example of what a Chicago-style Bibliography page typically looks like. Using standard formats for your entries enhances your credibility with academic readers, and alphabetizing your list helps fellow researchers quickly locate the sources that you refer to in the body of your text. For more formats & source types, visit http://www.dianahacker.com/resdoc/ or, for access to the full Chicago Manual of Style online (16th edition), visit z.umn.edu/chicagostyle (access provided by University of Minnesota Libraries). Every entry begins flush left; additional lines are indented 0.5” from the left margin. Label your page “Bibliography” in the center of the first line. Bibliography film or video work in an anthology online newspaper article short work from a website book with 2 or 3 authors book with one author journal article from a database (when DOI, or Digital Object Identifier, is available) online book with one author translated work entire website print journal article journal article from a database (using AN, or Accession Number, because no DOI is available) = electronic resource Chicago-style Bibliographies have oneinch margins all around. Single-space each entry and double-space between entries, unless your instructor prefers double-spacing throughout. Entries are alphabetical by author’s last name, or, if no author, by title. The Big Lebowski. DVD. Directed by Ethan Coen and Joel Coen. 1998; Universal City, CA: Universal Studios, 2008. Bruffee, Kenneth. “Collaborative Learning and the ‘Conversation of Mankind.’” In The Norton Book of Composition Studies, edited by Susan Miller, 545–62. New York: Norton, 2009. Fahim, Kareem. “School Official Apologizes for Removing Photo of Kiss.” New York Times, June 26, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/26/nyregion/26kiss.html. Lee, Taehohn. “The Financial Crisis and Refugees.” Immigration History Research Center. University of Minnesota. April 2, 2009. http://blog.lib.umn.edu/ihrc/immigration/2009/04/ the_financial_crisis_and_refug.html. Peregoy, Suzanne, and Owen F. Boyle. Reading, Writing, and Learning in ESL. New York: Longman, 1997. Puzo, Mario. The Godfather. New York: Signet, 1978. Redmon, Allen H. “How Many Lebowskis Are There? Genre, Spectatorial Authorship, and The Big Lebowski.” Journal of Popular Film & Television 40, no. 2 (2012): 52–61. doi:10.1080/ 01956051.2011.613422 Sherman, Ben. Medic!: The Story of a Conscientious Objector in the Vietnam War. 2002. Random House Digital, Inc, 2004. http://books.google.com/books?id=owO-MZI6WO0C. Tolstoy, Leo. Anna Karenina. Translated by Joel Carmichael. Toronto: Bantam Books, 1960. University of Minnesota. Immigration History Research Center. University of Minnesota. http://www.ihrc.umn.edu/. Villanueva, Victor. “Blind: Talking about the New Racism.” The Writing Center Journal 26, no. 1 (2006): 3–19. Wall, Brian. “‘Jackie Treehorn Treats Objects Like Women!’: Two Types of Fetishism in The Big Lebowski.” Camera Obscura 23, no. 69 (2008): 110–135. Academic Search Premier (36323375).

© Copyright 2025