Ainu names found in âGishi Wa-jin denâãéå¿å人ä¼ã

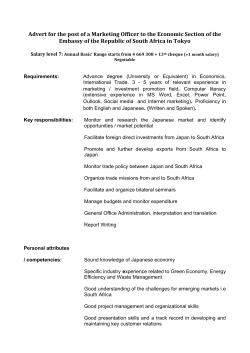

52 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Ainu names found in “Gishi Wa-jin den”「魏志倭人伝」 Tresi Nonno MA in sociocultural anthropology, independent scholar; Chiba, Japan; e-mail: tresi_nonno@hotmail.com Abstract Generally it has been thought that personal names found in the text of “Gi-shi Wa-jin den” can be interpreted through Early Old Japanese. However, until Kofun period there was no wide and regular spread of ‘Korean’ technologies so it’s possible to doubt that Early Old Japanese existed in the epoch of Yayoi. From the other hand wide spread of Ainu toponyms in Western Japan in Jōmon and Yayoi is a common place so interpreting names through Ainu language can be perspective. Having reconstructed original pronunciation of names I realized that names with kǝw/ko/hu endings are met only among names of higher nobility. These endings are supposed to be variants expressing the same word that i.e.: kur “respected being/person” that is usual ending in names of mythological heroes in modern Ainu folklore narratives and could probably be a component of aristocratic names in the epoch of Yamatai. Key words: Gishi Wajin den; Yamatai; Ainu; queen Himiko Problem introduction “Gi-shi wa-jin den” 魏志倭人伝 “Report of Wa in the book of Wei” or “Wa-jin den” 倭人伝 “Report of Wa people” are conventional short titles used to denote a part of chronicle of Wei kingdom (220–265 AD), in which are described some territories neighbor to China, and among others are described states existed in Japanese archipelago in 2nd – 3rd centuries AD. Short title is used as far as full title is rather long and complicated: San-goku-shi gi-sho maki san jū ugan senbi tōi den wa-jin-jō 『「三国志」「魏書」巻三十、「烏桓・鮮卑・東夷伝」「倭人 条」』“Chronicle of Three Kingdoms, 30th volume of Wei book, part of Wuhuan, Xianbei and Dongyi, chapter of Wa people”. “Chronicle of Three Kingdoms” covers the period of Late Eastern Han dynasty (184 – 220 AD) and the period of three kingdoms (220 – 280 AD). Three kingdoms were: Wei, Shu and Wu (pic. 1); they appeared after the decay of Late Eastern Han. The chronicle was written by Chen Shou in 3rd century AD on the base of local chronicles and reports. Text of the chronicle is considered as official and authoritative document of the epoch. “Wa-jin den” seems to be written by someone who really visited Japanese archipelago as far as distances are expressed quite closely to modern estimations. In “Wa-jin den” there are some names and toponyms which are written down by meaningless sets of Chinese signs used phonetically. Current paper is devoted people’s names There is a presupposition that personal names represented in “Wa-jin den” are words of Old Japanese. For instance, name of queen of Yamatai, that is pronounced as [Himiko] in modern 53 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Japanese and was pronounced as [Pimiko] in Early Old Japanese; the name is generally supposed to be a typical Japanese female name with female ending ko 子(literary “child”) and it is usually interpreted as: 姫子 Pimeko “princess”/ “noble lady”; or 日巫女 Pimiko “prophetess of kami of Sun” (Tsunoda 1951). I consider such interpretations as rather naïve since they don’t take into account the possibility that those names could be words of other languages and the fact that Old Japanese didn’t exist yet in that epoch. Pic. 1 Map representing three kingdoms (source: https://chinahistorysg.wordpress.com/tag/wei/ – accessed May 2015) Why is it possible to doubt that personal names met in Wa-jin den are words of Old Japanese? Main objection against Japanese origin of names is the absence of Japanese language in that epoch. Before contemporary history spreading of certain language should correlate with 54 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) spreading of correspondent culture: if we don’t see wide and regular spread of certain technologies then there was no correspondent language. In the case of Japanese facts are the following: Japanese language is a language of Buyeo stock; languages of Buyeo stock are actually closely connected with ‘Korean’ cultures. Despite it is often thought that early Japanese language existed yet in the epoch of Yayoi we don’t see any serious ‘Korean’ influence before Kofun period (4 – 6 centuries AD). In the period of Kofun we can see regular and wide spread of ‘Korean’ technologies in Japanese archipelago but we don’t see their regular spread before All items of ‘Korean’ origin seen in the epoch of Yayoi are mostly elements of cargo cult, i.e. copying of some items without due understanding of their true meaning; such are, for instance, famous dōtaku bells (pic. 2) that had no practical use but were used just as ritual objects; while their prefigurations obviously had practical usage (pic. 3). Pic. 2. Dōtaku; left is 52.8 cm height; right is 45 cm : (source: http://www.rekihaku.ac.jp/english/outline/publication/rekihaku/121/witness.html – accesed May 2015) Pic. 3. Dōtaku prefigurations; from the left: 2,400 years old, site of excavation unknown, height: 22.3 cm; 2,400 years old, Korea, height: 15.9 cm; 3,500 years old China, height: 9.1 cm; 3,700 years old China, height: 8.4 cm; 3,900 years old, China, height: 2.6 cm (source: http://www.rekihaku.ac.jp/english/outline/publication/rekihaku/121/witness.html accessed May 2015) – 55 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Metal industry and metal items were exotic in the epoch of Yayoi while in the epoch of Kofun we can see regular spreading of these issues and other ‘Korean’ technologies (pic.: 4 – 9). Pic. 4 Korean swords with ring pommels 5th – 6th century (source: 2015) http://www.martialartsplanet.net/forums/showthread.php?t=105468 – accessed May Pic. 5 Kofun swords (source: http://www.forensicfashion.com/500KofunWarriorSword.html – accessed May 2015) 56 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Pic. 6. Korean 5th century personal armor (source: http://www.digplanet.com/wiki/Korean_armour – accessed May 2015) Pic. 7. Kofun 5th century personal armor (source: http://www.forensicfashion.com/500KofunWarrior.html – accessed May 2015) 57 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Pic. 8 Korean Tomb Painting 4th century (source: http://www.art-andarchaeology.com/korea/goguryeo/an01.html – accessed May 2015) Pic. 9 Late Kofun tomb painting (source: http://www.asukanet.gr.jp/asukahome/ASUKA2/TAKAMATUTUKA/takamatutuka.html – accessed May 2015) 58 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Also if we take an impartial look at architecture of Yoshinogari site (pic. 10) that was settlement of Yayoi epoch and at Sannai-Maruyma settlement (pic. 11) of late Jōmon we see almost no differences; it isn’t a great mistake to say architecture of Yoshinogari was just development of that of Sannai-Maruyama. Pic. 10 Yoshinogari site (source: http://tabisite.com/gallery_as/japan/japanen.shtml – accessed May 2015) Pic. 11 Sannai-Maruayama site (source: http://tabisite.com/gallery_as/japan/japanen.shtml – accessed May 2015) 59 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Pic. 12. Map representing location of Sannai-Maruyama and Yoshinogari sites (drawn by the author after Google map screenshot) Also If we take a look at Yayoi pottery and at pottery of Late Jōmon we also don’t see difference between two potteries (Pic.13, Pic. 14) be we can rather say that pottery of Yayoi is a continuation of late Jōmon pottery with just slight continental influences. Thus it can be concluded there was no Japanese language in the epoch of Yayoi yet and so it can’t be perspective to interpret names of Wa-jin den through Japanese language. 60 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Pic. 13 Late Jōmon pot (photo source http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/maibun/english/artifact-en1.html – accessed May 2015) Pic. 14 Early Yayoi pots (photo source http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/maibun/english/artifact-en1.html – accessed may 2015) 61 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Why is it possible to suppose that certain personal names met in Wa-jin den can be words of Ainu language? The fact that there are many toponyms which are words of Ainu origin in the places located outside of area where Ainu live in recent times (Chamberlain 1887) means that Ainu language was widely spread in ancient epochs. These toponyms obviously were spread in the epoch preceding wide migration of Buyeo languages speaking people, i.e.: before Kofun epoch. Due to this case it seems to be rather logical and correct to interpret names in “Wa-jin den” through Ainu language. In the texts of Wa-jin den we can find the following personal names: 1. 台与 (traditional: 臺與) [ʔjitjɨăh]1 – girl who was chosen by Yamatai nobility to be the ruler after Pimiko death; 2. 伊支馬 [ʔjittɕiămaɨ’]/[ʔjittɕiămɛ:’]/[ʔjittɕimaɨ’]/[ʔjittɕimɛ:’] – a person who was in the palace of Pimiko; 3. 狗古智卑狗 [Kewkɔ’triăhpjikew]/[Kewkɔ’triahpjiĕkew]/[Kewkɔ’trihpjikew]/[Kewkɔ’trihpjiĕkew] – ruler of [Kewnɔ] kingdom 狗奴国; 4. 彌彌[Mjiĕmjiĕ]/[Mjimji] – ruler of [Dǝwmaɨ’]/[Dǝwmɛ:’] kingdom 投馬国; 5. 彌彌那利[Mjiĕmjiĕnalih]/[Mjimjinalih] – assistant of [Mjimji]; 6. 弥馬升[Mjimaɨ’ɕiŋ] /[Mjiĕmaɨ’ɕiŋ]/[Mjimɛ:’ɕiŋ]/[Mjiĕmɛ:’ɕiŋ] – person who was in the palace of Pimiko; 7. 弥馬獲支 [Mjimaɨ’ɣwǝɨjktɕi]/[Mjimaɨ’ɣwǝɨjkɕiă]/[Mjimaɨ’ɣwɛ:jktɕi]/ [Mjimaɨ’ɣwɛ:jktɕiă] [Mjimɛ:’ɣwǝɨjktɕi] / [Mjimɛ:’ɣwǝɨjkɕiă] / [Mjimɛ:’ɣwɛ:jktɕi] / [Mjimɛ:’ɣwɛ:jktɕiă] / [Mjiĕmaɨ’ɣwǝɨjktɕi] / [Mjiĕmaɨ’ɣwǝɨjkɕiă] / [Mjiĕmaɨ’ɣwɛ:jktɕi] / [Mjiĕmaɨ’ɣwɛ:jktɕiă] / [Mjiĕmɛ:’ɣwǝɨjktɕi] / [Mjiĕmɛ:’ɣwǝɨjkɕiă] / [Mjiĕmɛ:’ɣwɛ:jktɕi] / [Mjiĕmɛ:’ɣwɛ:jktɕiă] – person who was in the palace of Pimiko; 8. 爾支[Ɲjĕtɕiă]/[Ɲjĕtɕi]/[Ɲitɕiă]/ [Ɲitɕi]– ruler of [ʔjitɔ] kingdom 伊都国; 9. 奴佳鞮 [Nɔkaɨjtɛj]/[Nɔkɛ:jtɛj] – person who was in the palace of Pimiko; 10. 柄渠觚[Piajŋh’gɨĕkɔ] – assistant of [Ɲitɕi] in [ʔjitɔ] kingdom; 11. 卑狗 [Pjiĕkǝw]/[Pjikǝw] – ruler of [Twǝjhxǝj] kingdom 対海国; [Twǝjxǝj] is thought to be former name of Tsushima; and ruler of [ʔjitdajh] kingdom 一大, the kingdom of [ʔjitdajh] is thought to be modern Iki island 壱岐; 12. 卑弥呼[Pjiĕmjiĕhu]/[Pjiĕmjihu]/[Pjimjiĕhu]/[Pjimjihu] – queen of [Jiamaɨ’thǝj]/[Jiamɛ:thǝj] kingdom 邪馬台国; 13. 卑奴母離 [Pjiĕnɔnɔmɔliǝ]/[Pjinɔmɔliǝ]/[Pjiĕnɔmɔli]/[Pjinɔmɔli] – assistant of [Pjiekǝw] in the kingdoms of [Twǝjhxǝj] and [ʔjitdajh], assistant of [Zi’maɨ’kɔ] in the kingdom of [Nɔ], assistant of [Tamɔ] in the kingdom of Putmjiĕ; 14. 泄謨觚 [Siatmakkɔ] – assistant of [Ɲitɕi] in [ʔjitɔ] kingdom; 15. 多模 [Tamɔ] – ruler of [Putmjiĕ]/[Pǝtmjiĕ] kingdom 不彌国; 16. 兒馬觚 [Zi’maɨ’kɔ]/[Zi’mɛ:’kɔ] – ruler of [Nɔ] kingdom 奴国. 1 Transcriptions of original Late Han pronunciation of names were made with the use of Pulleyblank 2002 62 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) Pic. 15 Map representing approximate location of kingdoms mentioned in text (drawn by the author after Google map screenshot) Thus we have 16 personal names: 4 names are supposed to be names of servants/plain people/ lower nobility, 12 names are obviously names of nobility (rulers and assistants), and there are 8 names of rulers (highest nobility) among nobility names. Especially interesting in this context is distribution of names with kǝw/ko/hu endings: names with such endings are completely absent among names of servants while there are 50% of such names among nobility names. I suppose these endings kǝw/ko/hu are actually variants of the same morpheme. As far as names with kǝw/ko/hu endings are represented among names of nobility only, I suppose that it is possible to state that these endings could be markers of nobility. Also I suppose these endings kǝw/ko/hu are actually variants of the same morpheme. I suppose that these variants originated from Ainu word kur “man”, “person”, “respected being/person”; in 63 CAES Vol. 1, № 2 (May 2015) modern Ainu kur is usual ending used in names of kamuy – “super human beings” or mythological heroes, that can be easily seen in Ainu folklore narratives: Cep-atte-kur – “Being who produce fish” or Rap-us-nupur-kur “Powerful being with wings”, i.e.: “dragon”. As far as Late Han Chinese had no appropriate means to express original pronunciation we have quite rough approximation to the original and have different variants. Ainu had a tradition to give child names and then adult names if something notable happened adult names; adult names expressed certain characteristic features of person (Ohnuki-Tierney 1984). I think it’s possible to suppose that in ancient times beside the tradition of adult names existed also tradition of aristocratic names that were given to most outstanding representatives of noble class while names of the rest nobility didn’t differ much from those of plain people. It’s interesting to note that in modern Ainu kur ending is used in male names only while it seems to be gender indifferent in ancient time. References Chamberlain B. H. 1887. The Language, Mythology, and Geographical Nomenclature of Japan Viewed in the Light of Aino Studies. Tokyo Imperial University, Tokyo Ohnuki-Tierney E. 1984. Ainu of North-West Cost of Southern Sakhalin. Waveland Press, N.-Y. Pulleyblank E. G. 2002. Lexicon of reconstructed pronunciation: In Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese and Early Mandarin. UBC Press, Vancouver Sangoku shi Gi-sho Wa-jin den『三国志魏書』倭人伝 (Report of Wa people in the book of Wei) http://members3.jcom.home.ne.jp/sadabe/kanbun/wakoku-kanbun1-gisi.htm – accessed May 2015 Tsunoda R. 1951. Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties, P.D. and Ione Perkins, South Pasadena

© Copyright 2025