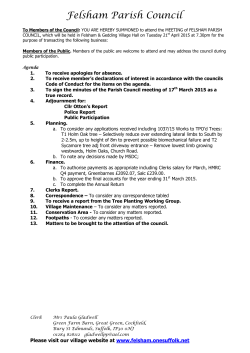

Agenda reports pack PDF 6 MB - Committees