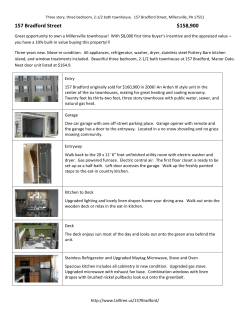

CNet how to develop oral