HOW TO PROPERLY HANDLE A REQUEST FOR A REASONABLE ACCOMMODATION/MODIFICATION ISAAC ROITMAN

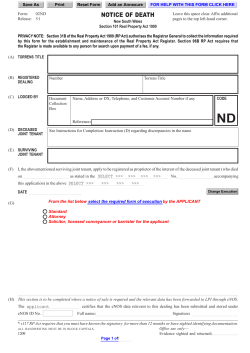

HOW TO PROPERLY HANDLE A REQUEST FOR A REASONABLE ACCOMMODATION/MODIFICATION ISAAC ROITMAN ATTORNEY AT LAW AUSTILL, LEWIS & PIPKIN, P.C. 600 Century Park South Suite 100 Birmingham, Alabama 35226 Telephone: (205) 870-3767 Facsimile: (205) 870-3768 Mobile, Alabama Office: Commerce Building Suite 508 118 North Royal Street Mobile, Alabama 36602 Telephone: (251) 431-9006 Facsimile: (251) 431-0555 Website: www.maplaw.com E-mail Address: i-roitman@maplaw.com I. Introduction 1 There are three primary statutes that prohibit discriminatory practices against individuals classified as disabled or handicap in the context of housing: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Fair Housing Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 states: “No otherwise qualified individual with a disability in the United States. . . shall, solely by reason of her or his disability, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, service or activity receiving federal financial assistance or under any program or activity conducted by any Executive agency or by the United States Postal Service.” This means that Section 504 prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in any program or activity that receives financial assistance from any federal agency, including the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The Section 504 regulations define “recipients of federal financial assistance” as any State or its political subdivision, any instrumentality or a state or its political subdivision, any public or private agency, institution, organization, or other entity or any person to which federal financial assistance is extended for any program or activity directly or through another recipient, including any successor, assignee, or transferee of a recipient, but excluding the ultimate beneficiary of the assistance. Thus, a HUD funded public housing authority, or a HUD funded nonprofit developer of low income housing is a recipient of federal financial assistance and is subject to Section 504's requirements. However, a private landlord who accepts Section 8 tenant-based vouchers in payment for rent from a low income individual is not a recipient of federal financial assistance. Similarly, a family that receives Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) or HOME funds for the rehabilitation of an owner-occupied unit is also not a recipient because it is the ultimate beneficiary of the funds. Therefore, federally assisted housing programs are covered by Section 504. The Fair Housing Act’s definition of “handicap” is virtually identical to the broad definition of “disability” that governs claims under Section 504 with the intent that the Fair Housing Act’s coverage would be interpreted in a manner that is consistent with the regulations interpreting the Rehabilitation Act. Thus, claims that would be cognizable under Section 504 may now also be brought under the Fair Housing Act, whose generous scope concerning standing, relief, and practices covered is 2 likely to make it the principal legal resource for challenging handicap discrimination in federally assisted, as well as private, housing. Please note that although Section 504 imposes greater obligations than the Fair Housing Act in certain areas (e.g., providing and paying for reasonable accommodations that involve structural modifications to units or public and common areas), the principles discussed under the Fair Housing Act generally apply to requests for reasonable accommodations to rules, policies, practices, and services under Section 504. The Fair Housing Act (FHA) prohibits discrimination in housing practices on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, familial status, and disability. The Act prohibits housing providers from discriminating against persons because of their disability or the disability of anyone associated with them and from treating persons with disabilities less favorably than others because of the disability. The Act also requires housing providers “to make reasonable accommodations in rules, policies, practices, or services, when such accommodations may be necessary to afford such person(s) equal opportunity to use and enjoy a dwelling.” The Act applies to the vast majority of privately and publicly owned housing including housing subsidized by the federal government or rented through the use of Section 8 voucher assistance. HUD’s regulations implementing the disability discrimination prohibitions of the Act may be found at 24 C.F.R. 100.201 - 205. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), in most cases, does not apply to residential housing. Title III of the ADA prohibits discrimination against persons with disabilities in commercial facilities and public accommodations. However, Title III of the ADA covers public and common use areas at housing developments when these public areas are, by their nature, open to the general public or when they are made available to the general public. For example, it covers the rental office, since, by its nature, the rental office is open to the general public. In addition, if a day care center, or a community room is made available to the general public, it would be covered by Title III. Title III applies, regardless of whether the public or common use areas are operated by a federally assisted provider or by a private entity. However, if the community room or day care center were only open to residents of the building, Title III would not apply. Title II of the ADA covers the activities of public entities (state and local governments). Title II requires “public entities to make both new and existing 3 housing facilities accessible to persons with disabilities.” Housing covered by Title II of the ADA includes public housing authorities that meet the ADA definition of “public entity,” and housing operated by States or units of local government, such as housing on a State university campus. Please note that when the ADA is applicable to a residential housing project, it does not supersede Section 504, assuming that Section 504 is also applicable. Instead, where both laws apply to a housing project, the project must be in compliance with both laws. II. Determining whether an individual is handicap or disabled. A. Defining the protected class of handicap or disabled. The Fair Housing Act defines “handicap” as : (1) a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more of a person’s major life activities, (2) a record of having such an impairment, or (3) being regarded as having such an impairment. 42 U.S.C. § 3602(h). This definition is extremely broad and it is virtually identical to the one contained in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (29 U.S.C. § 705(9)(B)), and Congress clearly intended it to be “interpreted in a manner that is consistent with regulations interpreting” the similar provision in Section 504. 54 Fed. Reg. 3245 (Jan. 23, 1989). Please note that the 1988 Fair Housing Amendments Act added prohibitions against “handicap” discrimination to the Fair Housing Act. However, the Act’s definition of “handicap” is virtually identical to the definition of “disability” in the two other principal federal statutes that ban discrimination based on this factor, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. It is clear that “handicap” in the Fair Housing Act has the same meaning as “disability” in the Rehabilitation Act and the ADA. The Fair Housing Act does contain two narrow exceptions to its broad definition of “handicap.” The term does not apply to an individual solely because that individual is a transvestite nor does it include “current, illegal use of or 4 addiction to a controlled substance.” 42 U.S.C. § 3602(h). This latter exclusion does not eliminate protection for people who legally take drugs (e.g., for medical reasons) or for people who once were, but are no longer, illegal drug users. These limited exceptions reinforce the notion that the Fair Housing Act’s definition of “handicap” covers an extremely broad range of impairments. Furthermore, juvenile offenders and sex offenders, by virtue of that status, are not persons with disabilities protected by the statutory language. In addition, the statutory language does not protect an individual with a disability whose tenancy would constitute a “direct threat” to the health or safety of other individuals or result in substantial physical damage to the property of others unless the threat can be eliminated or significantly reduced by a reasonable accommodation. Part (1) of the definition includes three separate elements providing for coverage when an individual has a “physical or mental impairment” that “substantially limits” a “major life activity.” The latter phrase includes such functions as caring for one’s self, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning, and working. Some courts have also even held that “obtaining housing” and “living independently” may also be “major life activities” for purposes of the Fair Housing Act. All physical and mental impairments are included, which means that coverage extends far beyond such obvious examples as persons who use wheelchairs or are visually impaired to include those who are substantially limited by alcoholism, emotional problems, mental illness or retardation, and learning disabilities. Many of the difficulties associated with old age are also covered even though old age itself is not per se a disability. The phrase “physical or mental impairment” may also include various diseases, such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. The legislative history of the Fair Housing Act and court decisions under the Rehabilitation Act make clear that coverage also extends to persons suffering from communicable diseases, including AIDS and infection with HIV. Drug addiction (other than addiction caused by current, illegal use of a controlled substance) is also included. Therefore, while it appears that virtually any impairment may qualify as a handicap, only those that are severe enough to “substantially limit” a major life activity are within the statutory definition. “Substantially” here suggests “considerable” or “to a large degree” and “precludes impairments that interfere in 5 only a minor way” with one’s life activities. Relevant factors in determining substantiality include the impairment’s nature and severity, its expected duration, and the likely long-term impact resulting from the impairment. The Supreme Court has ruled that “substantially limits” means that “the determination of whether an individual is disabled should be made with reference to measures that mitigate the individual’s impairment.” Sutton v. United Airlines, Inc., 527 U.S. 471 (1999). In other words, individuals such as those with severe myopia that can be corrected by eyeglasses are not “substantially limited” by their condition and are thus not protected. Other conditions that would not qualify as disabilities if their effects can be curbed by using proper medication or other mitigating measures include diabetes and high blood pressure. On the other hand, individuals whose disabilities cannot be ameliorated without medication or other measures that produce substantially limiting side effects may be covered by the statute. In sum, the degree to which each individual’s impairment limits his or her activities must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, because the focus is not “general information about how an uncorrected impairment usually affects individuals, but rather on the individual’s actual condition.” See Murphy v. United Parcel Service, Inc., 527 U.S. 516 (1999); Albertson’s, Inc. v. Kirkinburg, 527 U.S. 555 (1999). Part (2) of the Fair Housing Act’s definition of “handicap” covers people who have a record of the kind of impairment identified in Part (1). This would include people who have a history of being handicapped, such as a former drug addict, and even those who have been misclassified as having a handicap. 24 CFR 100.201(c). Part (3) of the definition covers people who are regarded as having such an impairment. To come within this part of the definition, it is necessary that a housing provider “entertain misperceptions about the individual - it must believe either that one has a substantially limiting impairment that one does not have or that one has a substantially limiting impairment when, in fact, the impairment is not so limiting.” Therefore, people would be “regarded as” being handicapped for purposes of the statutes if they have a condition that does not substantially impair the major life activities but are treated by others as having such a limitation. Examples of Part (3) include persons who are discriminated against because they are elderly or are former addicts, because they tested positive for the virus that causes AIDS, or because they have lost some finger on one hand, even though these conditions may have no effect on their activities. 6 B. Individuals who constitute a direct threat. As previously mentioned, it is important to note that the Fair Housing Act does not protect an individual with a disability whose tenancy would constitute a “direct threat” to the health or safety of other individuals or result in substantial physical damage to the property or others unless the threat can be eliminated or significantly reduced by a reasonable accommodation. More specifically, exclusion of individuals based upon fear, speculation, or stereotype about a particular disability or persons with disabilities in general is not allowed. A determination that an individual poses a direct threat must rely on an individualized assessment that is based on reliable objective evidence in the form of current conduct or a recent history of overt acts. The assessment must consider: (1) the nature, duration, and severity of the risk of injury; (2) the probability that injury will actually occur; and (3) whether there are any reasonable accommodations that will eliminate the direct threat. In evaluating a recent history of overt acts, a housing provider must take into account whether the individual has received intervening treatment or medication that has eliminated the direct threat, in other words, a significant risk of substantial harm. In such a situation, the housing provider may request that the individual document how the circumstances have changed so that he no longer poses a direct threat. A housing provider may also obtain satisfactory assurances that the individual will not pose a direct threat during the tenancy. The housing provider must have reliable, objective evidence that a person with a disability poses a direct threat before excluding him from housing on that basis. In later sections of this paper, there are general examples outlining how this “direct threat” scenario can play out during the application process and during the tenancy of an individual. C. Information needed to determine the classification of a tenant as handicap or disabled. Another important aspect related to the classification of a disabled individual is what information may be requested by the housing provider during the application process and during the tenancy of a disabled individual. Under the Fair Housing Act, it is unlawful for a housing provider to (1) ask if an applicant for a dwelling has a disability or if a person intending to reside in a dwelling or anyone associated with an applicant or resident has a disability, or (2) ask about the nature 7 or severity of such persons’ disabilities. Housing providers may, however, make the following inquiries, provided that these inquiries are made of all applicants, including those with and without disabilities: * An inquiry into an applicant’s ability to meet the requirements of tenancy; * An inquiry to determine if an applicant is a current illegal abuser or addict of a controlled substance; * An inquiry to determine if an applicant qualifies for a dwelling legally available only to persons with a disability or to persons with a particular type of disability; and * An inquiry to determine if an applicant qualifies for housing that is legally available on a priority basis to persons with disabilities or persons with a particular disability. In terms of individuals who request reasonable accommodations, a housing provider is entitled to obtain information that is necessary to evaluate if a requested reasonable accommodation may be necessary because of a disability. If a person’s disability is obvious, or otherwise known to the provider, and if the need for the requested accommodation is also readily apparent or known, then the provider may not request any additional information about the requester’s disability or the disability-related need for the accommodation. If the requester’s disability is known or readily apparent to the provider, but the need for the accommodation is not readily apparent or known, the provider may request only information that is necessary to evaluate the disability-related need for the accommodation. Normally, a housing provider may not inquire as to the nature and severity of an individual’s disability. However, in response to a request for a reasonable accommodation, a housing provider may request reliable disability-related information that (1) is necessary to verify that the person meets the definition of disabled under the statutory language (has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities), (2) describes the needed accommodation, and (3) shows the relationship between the person’s disability and 8 the need for the requested accommodation. Depending on the individual’s circumstances, information verifying that the person meets the definition of disabled can usually be provided by the individual himself or herself. A doctor or other medical professional, a peer support group, a non-medical service agency, or a reliable third party who is in a position to know about the individual’s disability may also provide verification of a disability. In most cases, an individual’s medical records or detailed information about the nature of a person’s disability is not necessary for this inquiry. Once a housing provider has established that a person meets the definition of disability, the provider’s request for documentation should seek only the information that is necessary to evaluate if the reasonable accommodation is needed because of a disability. Such information must be kept confidential and must not be shared with other persons unless they need the information to make or assess a decision to grant or deny a reasonable accommodation request or unless disclosure is required by law. III. How to handle a request for a reasonable accommodation. A. Definition of a reasonable accommodation/modification. A reasonable accommodation is a change, adaptation, or modification to a policy, program, service, or workplace which will allow a qualified person with a disability to participate fully in a program, take advantage of a service, or perform a job. A reasonable modification is a structural change made to an existing premises occupied by a person with a disability in order to afford such a person the full enjoyment of the premises. Reasonable modifications can include structural changes to interiors and exteriors of a unit as well as common areas.1 1 Please note that I will occasionally use the term “reasonable accommodation” throughout this paper to refer to both a reasonable accommodation and a reasonable modification. 9 Reasonable accommodations may include those which are necessary in order for the person with a disability to use and enjoy a dwelling, including public and common use spaces. Since persons with disabilities may have special needs due to their disabilities, in some cases, simply treating them exactly the same as others may not ensure that they have an equal opportunity to use and enjoy a dwelling. It is unlawful to refuse to make reasonable accommodations to rules, policies, practices, or services when such accommodations may be necessary to afford persons with disabilities an equal opportunity to use and enjoy a dwelling. In order to show that a requested accommodation may be necessary, there must be an identifiable relationship between the requested accommodation and the individual’s disability. Whether a particular accommodation is “reasonable” depends on a variety of factors and must be decided on a case-by-case basis. The determination of whether a requested accommodation is reasonable depends on the answers to two main questions. First, does the request impose an undue financial and administrative burden on the housing provider? Second, would making the accommodation require a fundamental alteration in the nature of the provider’s operations? If the answer to either question is yes, the requested accommodation is not reasonable. However, even where a housing provider is not obligated to provide a reasonable accommodation because the particular accommodation is not reasonable, the provider is still obligated to provide other requested accommodations that do qualify as reasonable. For conventional housing communities, the general rule is that management is responsible for absorbing the costs of a reasonable accommodation (to the extent there is a cost associated with changing a policy or procedure) but that the tenant is responsible for paying for the costs related to a modification of a unit or common area. In practice, management will often agree to some type of cost sharing with the tenant as part of the interactive process expected under the Fair Housing Act. Furthermore, under the Fair Housing Act, the housing provider must allow the resident, at the resident’s expense, to make reasonable modifications when necessary. Typically, modifications at the resident’s expense are approved unless the resident cannot verify his need for the modification or the modification would create a structural problem within the building or the modification makes the facility unusable by other persons. The resident is responsible to pay for the cost of reasonable modifications, and if the alteration will interfere with the next resident’s use of the apartment, the resident must agree to return the interior of the apartment unit to its unaltered condition upon termination of the lease. Reasonable 10 modifications to the public or common use areas do not have to be returned to the original condition. Please note that a housing provider may condition permission for a modification on the tenant providing a reasonable description of the proposed modifications as well as reasonable assurances that the work will be done in a professional manner and that the tenant will obtain any required building permits for the work. Under these circumstances, the housing provider may not require an increased security deposit for residents who wish to make modifications, but the provider may negotiate an agreement that the resident pay into an interest-bearing escrow account, over a reasonable period, an amount of money not to exceed the cost of the restorations. The interest in any such account shall accrue to the benefit of the resident. As stated previously, housing that receives federal financial assistance is covered by both the Fair Housing Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Under the Section 504 implementing regulations, structural changes (reasonable modifications) needed by a tenant with a disability must be paid for by the housing provider unless providing them would be an undue financial and administrative burden or would represent a fundamental alteration of the program. In real terms, this means that such a housing provider may be required to spend funds in order to provide a legally required reasonable accommodation. And as stated later during this presentation, there are also times when the housing provider can also offer to meet the resident’s needs through an alternative or different accommodation. B. Requesting a reasonable accommodation/modification. A resident or an applicant for housing makes a reasonable accommodation request whenever he or she makes it clear to the housing provider that he or she is requesting an exception, change, or adjustment to a rule, policy, practice, or service because of his or her disability. The requester should explain what type of accommodation he or she is requesting and, if the need for the accommodation is not readily apparent or not known to the provider, explain the relationship between the requested accommodation and his or her disability. An individual with a disability should request an accommodation as soon as it appears that the accommodation is needed, however, requests may be made at any time. For example, requests may be made when an individual is applying for 11 housing, entering into a lease agreement, or occupying housing. Individuals who become disabled during their tenancy may request accommodations even if they were not disabled when they executed their lease agreements. An applicant or resident is not entitled to receive a reasonable accommodation unless he or she requests one. However, the statutes do not require that a request be made in a particular manner or at a particular time. A person with a disability need not personally make the reasonable accommodation request; the request can be made by a family member or someone else who is acting on his or her behalf. An individual making a request for a reasonable accommodation does not need to mention the statutory authority or use the words “reasonable accommodation.” However, the requester must make the request in a manner that a reasonable person would understand to be a request for an exception, change, or adjustment to a rule, policy, practice, or service because of a disability. Although a request for a reasonable accommodation can be made orally or in writing, it is usually helpful for both the resident and the housing provider if the request is made in writing. This will help prevent misunderstandings regarding what is being requested or whether the request was made. To facilitate the processing and consideration of the request, residents or prospective residents may wish to check with a housing provider in advance to determine if the provider has a preference regarding the manner in which the request is made. However, housing providers need to be aware that they must give appropriate consideration to reasonable accommodation requests even if the requester makes the request orally or does not use the provider’s preferred forms or procedure for making such requests. Even though a federally assisted housing provider is not required to adopt a formal procedure for processing requests for a reasonable accommodation, such a formal procedure will probably aid both the individual in making the request and the housing provider in assessing it and responding to it in a timely fashion. This will help prevent possible misunderstandings as to the nature of the request, and, in the event of later disputes, provide a record to show that the requests received proper consideration. But, once again, a housing provider may not refuse a request because the individual making the request did not follow any formal procedures that the provider has adopted. If a provider does adopt formal procedures for processing reasonable accommodation requests, the provider should ensure that the procedures, including any forms used, do not seek information that is not necessary 12 to evaluate if a reasonable accommodation may be needed to afford a person with a disability equal opportunity to use and enjoy a dwelling. A reasonable accommodation policy has two components. The first is the public statement of the housing provider’s priorities and intentions when working with applicants and residents with disabilities. This statement is similar to a fair housing policy statement, although it specifically addresses the needs of people with disabilities. For example: XYC Company does not discriminate against persons with disabilities in its services and structures. XYZ Company provides equal opportunity to all persons with disabilities and provides accommodations to meet the needs of persons with disabilities upon request if the accommodation is both reasonable and financially feasible. All requests for reasonable accommodations should be submitted in writing to the property manager. Upon request, the applicant/resident will also need to provide the name, address, and telephone number of a third party professional who will verify that the applicant/resident is disabled and needs the accommodation requested because of the disability. Management will respond to the request as quickly as possible. The second component of a reasonable accommodation policy is a written list of steps describing each step to be taken by the applicant/resident and the staff when a request is made for a reasonable accommodation. Careful development and consistent use of this list will ensure that each request is handled properly with adequate documentation. The steps to address a request for a reasonable accommodation should be included in the employee handbook and the community rules. Some of the issues that a housing provider may want to consider while developing this list of steps include: 1. Obtain the request in writing to ensure that all parties agree on the accommodation that has been requested and that documentation of the request exists for future reference. If the request is not made in writing, the specifics of the request may become an issue later. It may be useful to develop a reasonable accommodation form that applicants or residents can merely fill out, sign, and submit. 2. Require verification for all requests if the need is not visually obvious. 13 For example, when a resident who uses a wheelchair requests an assigned parking space close to the resident’s front door, the resident’s disability and need for the accommodation is probably obvious. In this situation, the housing provider should not want to obtain a verification from the third party. If a similar request is made by a person who does not have an obvious mobility impairment, the housing provider may need to require that the resident’s need for the accommodation be verified by the third party professional. The policy should state that all requests will be verified where the need is not visually obvious. 3. Address a request for a reasonable accommodation as soon as possible. Delay can be viewed as a denial. 4. Ensure consistency of responses to requests and provide objectivity by assigning someone within the company with the responsibility to review all requests for reasonable accommodations (usually the Section 504 Coordinator). 5. No request should be rejected without first offering some type of alternative in writing. Rather than merely rejecting the resident’s request, which permits the resident to accuse management of failing to accommodate, the housing provider’s offer of an alternative accommodation will provide the housing provider with a defense in the event of a complaint, even if the resident rejects the offer. 6. When the final determination is made on the resident’s request, be sure to document the decision and resulting actions in a letter to the resident. 7. Keep a list of all accommodations made on each property for future reference. Most importantly, a housing provider is only required to provide an accommodation if a request has been made and it is on notice of such a request. A provider has notice that a reasonable accommodation request has been made if a person, his or her family member, or someone acting on his or her behalf requests a change, exception, or adjustment to a rule, policy, practice, or service because of a 14 disability, even if the words “reasonable accommodation” are not used as part of the request. Lastly, a housing provider has an obligation to provide prompt responses to requests for reasonable accommodations. If a housing provider delays or fails to respond to a request for an accommodation, after a reasonable amount of time, that delay may be construed as a failure to provide a reasonable accommodation. At that juncture, a tenant or applicant may select to seek legal assistance or file a complaint with HUD. C. Responding to a request accommodation/modification. for a reasonable A housing provider can deny a request for a reasonable accommodation if the request was not made by or on behalf of a person with a disability or if there is no disability-related need for the accommodation. In addition, a request for a reasonable accommodation may be denied if providing the accommodation is not reasonable, i.e., if it would impose an undue financial and administrative burden on the housing provider or it would fundamentally alter the nature of the provider’s operations. As stated previously, the determination of an undue financial and administrative burden must be made on a case-by-case basis involving various factors, such as the cost of the requested accommodation, the financial resources of the provider, the benefits that the accommodation would provide to the requester, and the availability of alternative accommodations that would effectively meet the requester’s disability-related needs. A “fundamental alteration” is a modification that alters the essential nature of a provider’s operations. When a housing provider refuses a requested accommodation because it is not reasonable, the provider should discuss with the requester whether there is an alternative accommodation that would effectively address the requester’s disability-related needs without a fundamental alteration to the provider’s operations and without imposing an undue financial and administrative burden. If an alternative accommodation would effectively meet the requester’s disabilityrelated needs and is reasonable, the provider must grant it. Most importantly, an interactive process in which the housing provider and the requester discuss the requester’s disability-related need for the requested accommodation and possible alternative accommodations is helpful to all concerned because it often results in an effective accommodation for the requester that does not pose an undue financial 15 and administrative burden for the provider. There may be instances where a provider believes that, while the accommodation requested by an individual is reasonable, there is an alternative accommodation that would be equally effective in meeting the individual’s disability-related needs. In such a circumstance, the provider should discuss with the individual if she or he is willing to accept the alternative accommodation. In doing this, the housing provider should give primary consideration to the accommodation requested by the tenant or applicant because the individual with a disability is most familiar with his or her disability and is in the best position to determine what type of aid or service will be effective. If the housing provider does provide or suggest an alternative accommodation, the tenant or applicant may reject it if she or he feels that it does meet his or her needs. A failure to reach an agreement on an accommodation request is in effect a decision by the provider not to grant the requested accommodation. An important aspect of this process for housing providers to remember is that the requirement of a reasonable accommodation does not entail an obligation to do everything humanly possible to accommodate a disabled person - cost to the housing provider and benefit to the tenant merit consideration in the final determination. An accommodation should not extend a preference to handicapped residents as opposed to affording them an equal opportunity to use the dwelling unit. Also, housing providers are not precluded from inquiring into and verifying the asserted handicap or necessity of the accommodation sought by the tenant. If a housing provider is skeptical of a tenant’s alleged disability or the landlord’s ability to provide an accommodation to the tenant’s disability in rules, policies, procedures, and services pursuant to the applicable statutes and regulations, it is incumbent upon the housing provider to request documentation or open dialogue to avoid liability for refusing to provide such accommodation. IV. Examples of How to Handle Accommodation/Modification. Requests for a Reasonable This section will provide you with general examples of different types of requests for a reasonable accommodation and a guide as to how housing providers can handle these scenarios. The majority of requests for reasonable accommodation fall under three specific categories: 1. Physical alterations to a unit or common area. 16 2. How information is disseminated to a disabled individual. 3. Accommodations to certain policies and procedures of the housing provider. In providing these examples, please continue to note that how a housing provider responds to a request for a reasonable accommodation is to be analyzed on a caseby-case basis. These examples are solely to provide you with some guidance as to how general requests may be handled by a housing provider and what different scenarios may arise when a request is made by a prospective tenant or a tenant. A. General Examples 1. A housing provider has a policy of providing unassigned parking spaces to residents. A resident with a mobility impairment, who is substantially limited in her ability to walk, requests an assigned accessible parking space close to the entrance to her unit as a reasonable accommodation. There are available parking spaces near the entrance to her unit that are accessible, but those spaces are available to all residents on a first come, first serve basis. The provider must make an exception to its policy of not providing assigned parking spaces to accommodate this resident and provide the tenant an assigned accessible parking space in front of the entrance to her unit. 2. A housing provider has a policy of requiring tenants to come to the rental office in person to pay their rent. A tenant has a mental disability that makes her afraid to leave her unit. Due to her disability, she requests that she be permitted to mail her rent payment to the rental office as a reasonable accommodation. The housing provider must make an exception to its payment policy to accommodate this tenant. 3. A housing provider has a “no pets” policy. A tenant who is deaf requests that the provider allow him to keep a dog in his unit as a reasonable accommodation. The tenant explains that the dog is an assistance animal that will alert him to several sounds, including knocks at the door, sounding of the smoke detector, the telephone ringing, and cars coming into the driveway. The housing provide must make an exception to its “no pets” policy to accommodate this tenant. An older tenant has a stroke and begins to use a wheelchair. Her apartment 4. 17 has steps at the entrance and she needs a ramp to enter the unit. Her housing provider pays for the construction of a ramp as a reasonable accommodation to the tenant’s disability. In this type of example, please keep in mind other factors such as the requirement of who is to pay for the costs of the modification as well as whether the apartment unit is already considered fully accessible. 5. A tenant who recently began using a walker to get around has requested a move to a ground floor apartment unit. If a ground floor unit is available, the housing provider should provide it to the tenant as a reasonable accommodation. If no apartment unit is available, some other options to be provided include giving the tenant first choice of moving into the next available ground floor unit or allowing her to break her lease to move into another property that meets her needs. 6. A housing provider has received noise complaints about a child with a developmental disability. The housing provider has a right to establish reasonable noise regulations for the comfort and peaceful enjoyment of all residents. If the noise occurs during the day and is no louder than that made by other residents (or the typical child), it would be discriminatory to treat this child differently than others. However, if the noise is excessive or occurs after hours, the housing provider can advise the family that they must obey the noise policy. If they request some time to pursue an intervention to assist them with keeping the noise down during quiet hours, the housing provider should allow that as a reasonable accommodation. 7. An applicant who uses a walker prefers a third-story apartment to a ground floor unit. The housing provider does not have to install an elevator in the apartment unit if such a modification is cost prohibitive. 8. After a tenant was served with a summons for an unlawful detainer action, he requested a reasonable accommodation and expects the housing provider to work with him to help him remain a tenant. It is important to note that housing providers are required to provide reasonable accommodations at all points in th housing process, even at the eve of termination or tenancy. In line with this, please keep in mind that people with disabilities are not obligated to reveal their conditions and they might not do so unless they need a reasonable accommodation. It may be that a tenant realizes that a 18 reasonable accommodation is necessary only after he or she receives an eviction notice. B. Alternative Accommodations 1. As a result of a disability, a tenant is physically unable to open the dumpster placed in the parking lot by his housing provider for trash collection. The tenant requests that the housing provider send a maintenance staff person to his apartment on a daily basis to collect his trash and take it to the dumpster. Because ths housing provider is a small operation with limited financial resources and the maintenance staff are on site only twice per week, it may be an undue financial and administrative burden for the housing provider to grant the requested daily trash pick-up service. Accordingly, the requested accommodation may not be reasonable. If the housing provider denies the requested accommodation as unreasonable, the housing provider should discuss with the tenant whether reasonable accommodations could be provided to meet the tenant’s disability-related needs - for instance, placing an open trash collection can in a location that is readily accessible to the tenant so the tenant can dispose of his own trash and the provider’s maintenance staff can then transfer the trash to the dumpster when they are on site. Such an accommodation would not involve a fundamental alteration of the provider’s operations and would involve little financial and administrative burden for the provider while accommodating the tenant’s disability-related needs. C. 1. Fundamental Alteration A tenant has a severe mobility impairment that substantially limits his ability to walk. He asks his housing provider to transport him to the grocery store and assist him with his grocery shopping as a reasonable accommodation to his disability. The provider does not provide any transportation or shopping services for its tenants, so granting this request would require a fundamental alteration in the nature of the provider’s operations. The request can be denied, but the provider should discuss with the requester whether there is any alternative accommodation that would effectively meet the requester’s disability-related needs without fundamentally altering the nature of its operations, such as reducing the tenant’s need to walk long distances by altering its parking policy to allow a volunteer from a local community service organization to park her car close to the tenant’s unit so she can 19 transport the tenant to the grocery store and assist him with his shopping. 2. A tenant with a disability cannot do his own housekeeping and requests that the housing provider provide such services for his apartment unit. If the housing provider does not supply housekeeping services for all of its residents, a request for such services would not be reasonable because it would make a fundamental alteration in the nature of the housing provider’s operations. D. 1. Direct Threat A housing provider requires all persons applying to rent an apartment to complete an application that includes information on the applicant’s current place of residence. On her application to rent an apartment, an applicant notes that she currently resides in an apartment complex which the housing provider’s manager knows is a group home for women receiving treatment for substance abuse. Based solely on this information and the manager’s personal belief that substance abusers are likely to cause disturbances and damage property, the manager rejects the applicant. This rejection would be unlawful because it is based on a generalized stereotype related to a disability rather than an individualized assessment of any threat to other persons or the property of others based on reliable, objective evidence about the applicant’s recent past conduct. The housing provider may not treat this applicant differently than other applicants based on his subjective perceptions of the potential problems posed by her substance abuse by requiring additional documents, imposing different lease terms, or requiring a higher security deposit. However, the manager could have checked the applicant’s references to the same extent and same manner as he would have checked any other applicant’s references. If such a reference check had revealed objective evidence showing that the applicant had posed a direct threat to persons or property in the recent past and the direct threat had not been eliminated, the manager could then have rejected the applicant based on the direct threat. 2. A tenant at an apartment complex is arrested for threatening his neighbor while brandishing a baseball bat. The lease agreement contains a provision prohibiting tenants from threatening violence against other tenants. The 20 rental manager investigates the incident and learns during the course of the investigation that the tenant threatened the other resident with physical violence and had to be physically restrained by other neighbors. Following the apartment complex’s standard practice of strictly enforcing its policy, the rental manager issues to the tenant a notice of termination which is the first step in the eviction process. The tenant’s attorney contacts the rental manager and explains that the tenant has a psychiatric disability that causes him to be physically violent when he stops taking his medications. Suggesting that the tenant will not pose a direct threat to others if proper safeguards are taken, the attorney requests that the rental manager grant the tenant an exception to the apartment complex’s policy as a reasonable accommodation based on the tenant’s disability. The rental manager need only grant the reasonable accommodation if the tenant’s attorney can provide satisfactory assurance that the tenant will receive appropriate counseling and periodic medication monitoring so that he will not longer pose a direct threat during his tenancy. After consulting with the tenant, the attorney responds that the tenant is unwilling to receive counseling or submit to any type of periodic monitoring to ensure that he takes his prescribed medication. At that juncture, the rental manager may proceed with the eviction since the tenant continues to pose a direct threat to the health or safety of other residents. 3. Residents are complaining about the odd and threatening behavior of another resident. The housing provider issued the resident a violation notice and, subsequently, his sister notified the housing provider that he has a psychiatric disability. At that juncture, the housing provider is in a position to determine whether the resident’s behavior is only odd or whether it actually violates a tenancy rule. If the resident is merely eccentric, he has broken no rules. The housing provider should only issue a violation notice only when a rule has actually been violated. If the resident’s behavior is not only odd, but violates some rule (for example, he disturbs other residents by knocking on their doors in the middle of the night), then the housing provider needs to consider the effect, if any, of the resident’s disability on his behavior. If his disability is the cause of the behavior, it may be appropriate for the housing provider to inquire whether he or his sister have taken steps to minimize or eliminate the odd behaviors that result in the rule violations. However, keep in mind that 21 residents have also complained of threatening behavior. Fair housing laws do not require that a dwelling be made available to an individual whose tenancy would constitute a “direct threat” to the health or safety of other individuals. The housing provider should consider safety factors in deciding what to do and should determine whether the resident’s behavior is a direct threat. Please note that a direct threat is a significant risk of substantial harm to the health or safety of others that cannot be eliminated or reduced to an acceptable level through interventions allowed by a reasonable accommodation. This threat must be real and may not be based on generalizations or stereotypes about the effects of a particular disability. If the threat cannot be minimized or eliminated, the housing provider has the right to ask the resident to leave. However, if the resident’s family is pursuing treatment and/or other support interventions, the housing provider should allow them time to put those plans into place as an accommodation before asking him to leave. If the resident’s behavior poses an imminent direct threat to others while the plan is being put into place, appropriate authorities can be called to remove him. The following is a general overview of common housing accommodations and modifications that may be provided by housing providers to disabled tenants. These common or general examples do not only detail specific accommodations or modifications that may be requested but they may also provide housing providers with ideas of alternative accommodations or modifications that may be completed, if feasible: E. Vision Disabilities * * Allow a service animal. Read notices aloud to the resident or put notices in large print, audio tape, or Braille. Provide ample inside and outside lighting. Provide large print or Brailled numbers on the front door or common use areas. Remove protruding objects from hallways and outside pathways. Provide a non-slip, color-contrast strip on stairs. Hearing Disabilities * * * * F. 22 * * * * * * Provide a doorbell flasher. Provide a visual alarm system on smoke detectors throughout the property. Provide a sign language interpreter for resident meetings. If phones are provided, use a visual flasher attachment. Allow a service animal. Amplify a communications system. G. Cognitive Disabilities * * * * * * Write application, rental agreement, and notices in clear and simple terms. Explain rental agreement and tenancy rules. Show where the water shutoff valve is and when to use it. Show how to use appliances and common use areas. Make outside door locks or security locks simpler. Provide a reminder at the beginning of the month that the rent is due. H. Psychiatric Disabilities * * * * Allow a service or companion animal. Move a resident to a quieter unit, if requested. Place an application back on the waiting list (if the applicant missed the intake interview or got paperwork in late due to the disability). Upon request, provide intervention if the resident is being harassed. I. Physical Disabilities * * * * * * * * * Allow mail-in applications. Meet at an accessible location. Allow widening of doorways. Allow installation of bathroom grab bars. Allow a personal care attendant to live with the resident. Wrap kitchen and bathroom pipes with insulation. Install anti-skid tape on floors and stairs. Allow lowering of environmental controls. Allow lowering of closet rods. 23 * * * Provider lever door handles an automatic door closers. Move a resident to another floor or to the ground floor for easier mobility, if requested. Clear shrubs away from pathways and trim to eye level. J. HIV and AIDS * Move a resident to another floor or to the ground floor for easier mobility, if requested. Allow a personal care attendant to live with the resident in a two bedroom apartment. If requested, provide intervention if the resident is being harassed. Provide or allow a person from the community to educate other residents about the condition. * * * K. Environmental Disabilities * Use non-toxic fertilizers for landscape areas and non-toxic cleaning products for common areas. Allow removal of carpet from the apartment. Remove the fluorescent lights from the kitchen and bathroom. Post “No Smoking” signs in common use areas such as the office, hallways, lobby, and laundry room. * * * A general matter that may arise in some instances is when a tenant with a disability who has already been accommodated on several occasions keeps making accommodation requests and a housing provider questions how many accommodations they must provide to the tenant. The fact of the matter is that an individual with a disability can request reasonable accommodations or modifications whenever they are needed. For example, requests may be made when an individual is applying for housing, when entering into the rental agreement, while occupying housing, and even during the eviction process. Individuals who become disabled during their tenancy may request accommodations, even if they were not disabled when they moved into the apartment unit. Housing providers just need to evaluate each request in a timely and professional manner and document their interactions with the tenant. V. Analysis of Reasonable Accommodation claims in litigation. 24 A. General Overview The concept of “reasonable accommodations” in the Fair Housing Act is derived from regulations and case law interpreting Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. 29 U.S.C. § 794. Under the Fair Housing Act, a refusal to make a reasonable accommodation is discrimination under the act which prohibits disability discrimination in housing sales and rentals and in the terms, conditions, privileges, and services related thereto. It is important to note that a reasonable accommodation claim does not require a showing that the housing provider’s behavior was motivated by intentional discrimination. “Failure to reasonably accommodate” is an alternative theory of liability that is separate from intentional discrimination. Under the Fair Housing Act, the requirement of “reasonable” accommodations means that “feasible, practical modifications” must be made, but “extreme infeasible modifications are not required.” Preamble I, 53 Fed. Reg. 45003-04 (November 7, 1988). So, while a housing provider need not “do everything humanly possible to accommodate a disabled person,” an accommodation that “permits handicapped tenants to experience the full benefit of tenancy must be made unless the accommodation imposes an undue financial or administrative burden on a defendant or requires a fundamental alteration in the nature of its program.” Bronk v. Ineichen, 54 F.3d 425 (7th Cir. 1995); HUD v. Ocean Sands, Inc., Fair Housing - Fair Lending Rptr., 25,055, p.25,338 (HUD ALJ). This formulation of the test for reasonable accommodations is drawn from the language of an early Supreme Court decision interpreting the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which held that an accommodation would not be reasonable if it required “a fundamental alteration in the nature of the defendant’s program” or imposed “undue financial and administrative burdens” on the defendant. Southeastern Community College v. Davis, 422 U.S. 397 (1979). Many courts have used a similar formulation in deciding reasonable accommodations cases under the Fair Housing Act while other court opinions have suggested using a costbenefit analysis that weighs the accommodation’s cost to the defendant against its benefit to the plaintiff. Schwarz v. City of Treasure Island, 544 F.3d 1201 (11th Cir. 2008); Dadian v. Village of Wilmette, 269 F.3d 831 (7th Cir. 2001). 25 Regardless of the language used to describe the process, it is generally agreed that determining whether a particular accommodation is required is a highly fact specific endeavor requiring a case-by-case determination. In line with this, the courts generally agree that landlords and other targets of requests for reasonable accommodations may have to “shoulder certain costs. . . so long as they are not unduly burdensome.” The courts are divided, however, as to which party should have the burden of proof on the question of whether an accommodation is “reasonable” under the statutes. In the 11th Circuit, in order to prevail on a Fair Housing Act claim for denying a reasonable accommodation, a plaintiff must establish that (1) that he is disabled or handicapped within the meaning of the Fair Housing Act; (2) that he requested a reasonable accommodation; (3) that such an accommodation was necessary to afford him an opportunity to use and enjoy his dwelling; and (4) the defendant refused to make the requested accommodation. Schwarz v. City of Treasure Island, 544 F.3d 1201 (11th Cir. 2008).2 To make a prima facie claim under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the plaintiff must show that (1) he is an individual with a disability; (2) he is otherwise qualified to receive the benefits at issue; (3) he was denied the benefits of the program solely because of his disability; and (4) the program receives federal financial assistance. Phifer v. Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency, 2009 WL 2914336 (E.D. Cal.). 2 Please note that there are variations by the courts in the 11th Circuit as to the elements for this type of claim. For example, some of the decisions have outlined that in order for a plaintiff to prevail in a reasonable accommodation claim under the Fair Housing Act, the plaintiff must show: (1) he is disabled or handicapped within the meaning of the FHA, and that the defendants knew or should have known of that fact; (2) that the defendants knew that an accommodation was necessary to afford him equal opportunity to use and enjoy the dwelling; (3) such an accommodation is reasonable; and (4) the defendants refused to make the requested accommodation. See Hawn v. Shoreline Towers Phase I Condominium Ass’n, Inc., 2009 WL 691378 (N.D. Fla. 2009), aff’d, Hawn v. Shoreline Towers Phase Condominium Ass’n, Inc., 347 Fed. Appx. 464 (11th Cir. 2009). 26 Under Title II of the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act, the Plaintiff has the right to ask for injunctive relief among other damages. Compensatory damages are available in actions pursuant to Title II of the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act upon a showing of intentional discrimination. Wood v. President and Trs. of Spring Hill Coll. in City of Mobile, 978 F.2d 1214 (11th Cir. 1992); Badillo v. Ct. Adm’r Officer, 2005 WL 1027176 (M.D. Fla.). Punitive damages, however, are not available under Title II of the ADA or the Rehabilitation Act. Barnes v. Gorman, 536 U.S. 181 (2002). With regards to damages under the Fair Housing Act, a plaintiff may be awarded actual and punitive damages and may be granted relief, as the Court deems appropriate, in the form of any permanent or temporary injunction, temporary restraining order, or other order as the Court may deem to be appropriate, such as an order enjoining any defendant from engaging in such practice or ordering such affirmative action as may be appropriate. 42 U.S.C. § 3613(c). Nothing in the language of the act suggests any limitation on the type of “actual damages” a plaintiff may recover. Samaritan Inns, Inc. v. District of Columbia, 114 F.3d 1227 (D.C. Cir. 1997). Actual damages are defined as “an amount awarded to a complainant to compensate for a proven injury or loss.” Blacks Law Dictionary, 445 (9th Ed. 2009). The Supreme Court has also noted that an action for damages under the act “sounds basically in tort - the statute merely defines a new legal duty, and authorizes the courts to compensate a plaintiff for the injury caused by the defendants’ wrongful breach.” Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974). Courts have held that “actual damages” in housing discrimination cases include compensation for “inconvenience, mental anguish, humiliation, embarrassment, expenses, and deprivation of constitutional rights.” Morehead v. Lewis, 432 F.Supp. 674 (N.D. Ill. 1977). A plaintiff may also be awarded reasonable attorney’s fees and costs. 42 U.S.C. § 3613(c)(1). Punitive damages may also be awarded under the Fair Housing Act. 42 U.S.C. § 3613(c)(1). Punitive damages are available where “malicious,” “willful or wanton conduct can be shown;” “the final determination of whether punitive damages should be awarded is left to the trier of fact.” Morehead, supra at 679. Lastly, please note that under the section of the ADA prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations (Title III), private plaintiffs may not obtain monetary damages. Preventive relief, including an injunction or restraining 27 order, is the only remedy. 42 U.S.C. § 12188(a)(1). B. Eleventh Circuit case law. The first set of cases outlined in this section are recent decisions from the courts in the 11th Circuit with regards to reasonable accommodation claims: 1. Jacobs v. Concord Village Condominium X Ass’n, Inc., 2004 WL 741384 (S.D. Fla.) In this cause of action, the Plaintiff sought a declaratory judgment, preliminary injunctive relief, and permanent injunctive relief for discrimination against the housing provider in the provision of housing on the basis of a physical handicap. It was alleged by the Plaintiff that the Defendant intentionally discriminated against her on the basis of her physical handicap by refusing to provide a reasonable accommodation which limited her ability to use and enjoy her condominium in violation of the Fair Housing Act. More specifically, the Plaintiff was an 88 year old, physically handicapped victim of polio who resided alone at an apartment complex. In order to alleviate the excruciating pain that the Plaintiff was in while walking, she used a motorized tricycle. Soon after moving into the complex 22 years ago, the developer of the complex built the Plaintiff a plywood ramp so she could store her tricycle and recharge its battery in a closet on the ground floor which was four inches above the floor. Two years before the court decision, the ramp disappeared. A new ramp was constructed and it too soon disappeared. The Defendant then locked the door to the storage closet, refused to allow the Plaintiff to have another ramp installed, and denied her access to the tricycle in the storage closet. The Defendant defended its actions by asserting that it was contesting the Plaintiff’s physical handicap and whether her physical impairments and disabilities actually limited her major life activity of walking. The Court held that the Defendant had known of the Plaintiff’s handicap for the past 22 years and that it never had questioned it or had ever made any effort to contact any of the Plaintiff’s medical providers regarding her condition. The Court also held that the Defendant had known that the Plaintiff had been using a motorized tricycle on the property for the past 22 years and that the accommodation of the Plaintiff’s physical handicap by allowing her to re-install a ramp to access her motorized tricycle in the storage closet was necessary to afford 28 the Plaintiff an equal opportunity to use and enjoy her condominium. In sum, the Court ordered that the Defendant was permanently enjoined from prohibiting the Plaintiff to install, by securely bolting to the concrete floor, a plywood ramp so that the Plaintiff could freely store, access, and charge her motorized tricycle in the storage closet on the first floor of the Defendant’s building. Defendant was further ordered to provide the Plaintiff with a key to the storage closet in the event that the closet was locked so that the Plaintiff could have ready access to the tricycle. Lastly, in the event that the Plaintiff was no longer a resident at the complex or the Plaintiff’s physician determined that the use of the motorized tricycle was no longer medically necessary, the Plaintiff was ordered have the ramp removed and the flooring area restored to its original condition at the Plaintiff’s expense. 2. Hawn v. Shoreline Towers Phase I Condominium Association, Inc., 2009 WL 3004036 (C.A.11 (Fla.)) A condominium unit owner brought action against a condominium association and members of its board of directors for alleged violations of federal and state housing laws, as well as intentional infliction of emotional distress, based on the denial of his request to permit his service dog in his condominium unit. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida granted summary judgment for the Defendants and the condominium owner appealed. The Eleventh Circuit Court of Civil Appeals held that the Defendants could not have actually known of the owner’s disability and the necessity of a service animal and that there was evidence of discriminatory intent or impact from the Defendants’ posting of a “No Animals Allowed” sign. More specifically, the Court held that a condominium unit owner’s refusal to comply with subsequent requests of condominium association Defendants for reasonable documentation, after submitting a letter requesting that his dog be exempted from the condominium’s no pets policy as a “service animal,” prevented the Defendants from conducting a meaningful review of the owner’s application, and, therefore, the Defendant could not have actually known of the owner’s disability and the necessity of the service animal as was required for the Defendants to be liable for refusing to grant a reasonable accommodation under the Fair Housing Act. The owner’s letter included unclear explanations as to the 29 nature and extent of his disability and was wholly inconsistent with the reasons he provided in a previous letter for wanting the dog in his condominium unit. 3. U.S. v. Hialeah Housing Authority, 2010 WL 1540046 (S.D. Fla.) A public housing tenant failed to establish that a municipal housing authority knew of the tenant’s disability and that his requested accommodation was necessary. A doctor’s letter in response to the housing authority’s request for additional medical documentation lacked any explanation as to the extent and nature of the tenant’s diagnosis and any reference to the tenant’s alleged limited ability to climb stairs. Furthermore, instead of requiring additional time to substantiate his alleged disability with medical records, the tenant, while represented by counsel, chose to abandon his effort to obtain a reasonable accommodation by settling a state court eviction action and vacating his unit. C. General case law throughout the United States. The second set of cases outlined in this section are from jurisdictions across the country with the analysis centered on public housing and claims made under Section 504. 1. Powers v. Kalamazoo Breakthrough Consumer Housing Co-op, 2009 WL 2922309 (W.D. Mich.) The District Court held that a genuine issue of material fact existed as to whether an apartment tenant suffering from osteoarthritis and diabetes was handicapped. Therefore, summary judgment was precluded on the issue of whether the apartment complex was required to provide the tenant with a reasonable accommodation under the Fair Housing Act. The tenant had requested a room on the first floor and had documented evidence that she suffered from shortness of breath, degenerative arthritis in both knees, and difficulty performing orthopedic maneuvers. 2. Reyes v. Fairfield Properties, 661 F.Supp.2d 249 (E.D. N.Y. 2009) An African-American mother of an infant daughter with cerebal palsy who was permanently required to use a wheelchair brought an action against the property management agency and its director of leasing, the property manager and 30 assistant director, alleging discrimination and retaliation on the basis of disability and race in connection with their housing. The federal claims that were filed included claims under the Fair Housing Act and general state law claims. The Defendants moved to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction and failure to state a claim. With regards to the federal claims, the District Court held that the Plaintiffs failed to state a claim under the FHAA reasonable accommodations provision that the defendants were obligated to undertake wholly new construction or modify existing facilities by replacing steps with ramps or widening doors. Also, the claims under the FHAA reasonable accommodations provision survived dismissal to the extent the claims were based on the Defendants’ alleged practice of keeping driveways and the parking lot in state of disrepair and their alleged policy regarding parking spaces. Lastly, the construction and design requirements of FHAA handicap discrimination provision were inapplicable and the Plaintiffs’ allegations of causal connection between the protected activity and adverse action were sufficient for the FHAA retaliation claim to survive motion to dismiss. 3. Solivan v. Valley Housing Development Corp., 2009 WL 3763920 (E.D. Pa.) A county housing authority was not entitled to summary judgment on a disability discrimination claim because an apartment tenant presented sufficient evidence to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the housing authority failed or refused to provide her with a reasonable accommodation as required by law. The tenant presented evidence that a first floor apartment was vacant five months before her accident, but that the housing authority failed to timely inspect and repair the vacant apartment in order to make it available until after her accident. Further, the housing authority did not submit sufficient proof to establish that another tenant was listed ahead of her on a waiting list for first floor apartments. 4. Bowman v. Waterside Plaza, L.L.C., 2010 WL 2873051 (S.D.N.Y.) A pro se Plaintiff was a resident of a one-bedroom apartment in the Waterside Plaza housing complex. She commenced lawsuits, that were eventually consolidated, against Waterside Plaza, LLC and two of its representatives, as well as against the New York City Housing Preservation and Development Corporation (“HPD”) and one of its employees. The claims centered on a complaint that she 31 had not been transferred to a larger, two-bedroom apartment to accommodate a physical disability from which she claimed she suffered. At this stage of the litigation, the Plaintiff had stipulated to the dismissal of the Waterside defendants and the HPD Defendants had moved to dismiss the complaints against them for failure to state a claim. The Plaintiff was a recipient of Section 8 housing subsidies which were provided by HUD and funneled through a local housing agency, HPD. HPD moved to dismiss the complaint as against them based on the assertion that HPD had no authority to grant or deny a transfer of apartments as requested by the Plaintiff. The Court held that the Plaintiff’s claims against HPD could not proceed because there was no legal authority for the notion that HPD, as a designated local agency under the Section 8 program, had any legal authority to require the private landlord to provide her with an apartment of a given size or indeed provide her with an apartment at all. The Court further held that there was no statute which authorizes a local public housing agency to compel a private landlord to provide an apartment to someone simply because that person has a Section 8 voucher to subsidize the rent. 32 33 34

© Copyright 2025