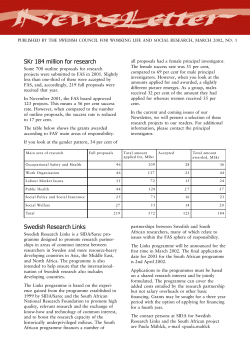

How to enter Brazil 2014 From a Market Knowledge perspective