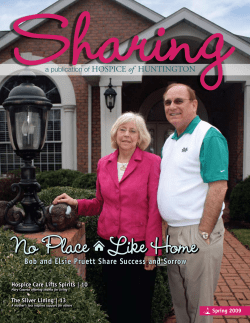

Document 2767