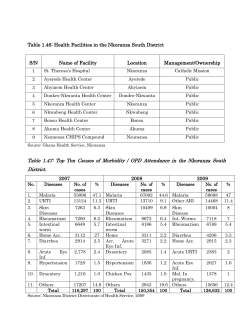

Disease surveillance for Malaria