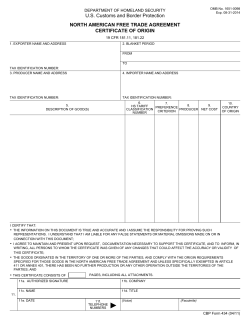

Effects of North American Free Trade Agreement on Agriculture