Plunging Into Perl While Avoiding the Deep End (mostly)

Plunging Into Perl

While Avoiding the Deep End

(mostly)

Some Perl nomenclature

PERL – Practical Extraction and Report

Language

Some Perl nomenclature

PERL – Practical Extraction and Report

Language

PERL – Pathologically Eclectic Rubbish

Lister (if you’re so inclined)

Some Perl nomenclature

PERL – Practical Extraction and Report

Language

PERL – Pathologically Eclectic Rubbish

Lister (if you’re so inclined)

TMTOWTDI – There’s More Than One Way

To Do It

Some Perl attributes

it’s a scripted language, not compiled faster, easier development

runs plenty fast for most things

Some Perl attributes

it’s a scripted language, not compiled faster, easier development

runs plenty fast for most things

Loose variable typing both good and bad,

but mostly good

Your first program

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

print "Hello, World\n";

“Protecting” your program (Unix)

By default, your program is

not executable.

chmod 744 your_program

You can execute it as owner

of the file, anyone else can

only read it.

Variables

$name

can be text or number:

a character,

a whole page of text,

or any kind of number

context determines type

can go “both” ways

Variables, array of

@employee

Array of $employee variables

$employee[0]

$employee[1]

etc.

Variables, hash of

$lib{‘thisone’} = “2 days”;

$lib{‘thatone’} = “5 days”;

Thus can use

$grace_period = $lib{$libname}

when $libname is thatone,

$grace_period is 5 days

Variables, list of

($var1, $var2, $var3) =

function_that_does_something;

This function returns a list of elements.

A list is always inside parentheses ().

Variables, assigning a value to

$var = value or expression

$array[n] = something;

@array = (); # empty array

%hash = ();

# empty hash

Can be done almost anywhere, anytime.

Variable scope, and good practices

use strict;

Requires that you declare all

variables like this:

my $var;

my $var = something;

my @array = ();

Also makes Perl check your code.

Best Practices!

Variable scope, and good practices

use strict;

my $var;

my $var = something;

my @array = ();

A variable declared like this is

visible throughout your program.

Best Practices!

Variable scope, and good practices

use strict;

my $var;

my $var = something;

my @array = ();

A “my” declaration within code grouped

within { and } is visible only in that

section of code; it does not exist

elsewhere.

Best Practices!

Scope: where in a program a variable exists.

File input and output (I/O)

Using command line arguments

Usage:

program.pl infile outfile

$ARGV[0] $ARGV[1]

String manipulation & other stuff

substring function

String manipulation & other stuff

a better substring example

String manipulation & other stuff

index function, find the location of a string in a

string

String manipulation & other stuff

The split function. Here we split string $l into

pieces at every space character.

Less common usage: take only 1st 2 pieces.

String manipulation & other stuff

find “db ratio” anywhere in $l

Actually, the 2nd statement should be:

$l =~ s/^ +//;

The ^ means start looking at the start of

the line.

String manipulation & other stuff

Instead of using $inline[n], $inline[n+1], etc.,

to refer to elements of array @inline, here we

can refer to @inline’s elements via $l in this

example. Often makes for clearer and simpler

code.

String manipulation & other stuff

An often convenient way of populating an array.

String manipulation & other stuff

Given

$stuff = “this is me”;

These are not equivalent:

“print $stuff”

‘print $stuff’

`print $stuff`

String manipulation & other stuff

Given

$stuff = “this is me”;

These are not equivalent:

“print $stuff” is “print this is me”

‘print $stuff’

`print $stuff`

String manipulation & other stuff

Given

$stuff = “this is me”;

These are not equivalent:

“print $stuff” is “print this is me”

‘print $stuff’ is ‘print $stuff’

`print $stuff`

String manipulation & other stuff

Given

$stuff = “this is me”;

`print $stuff` would have the

operating system try to execute the

command <print this is me>

String manipulation & other stuff

This form should be used as

$something = `O.S. command`

Example: $listing = ‘ls *.pl`;

The output of this ls command is

placed, as possibly a large string, into

the variable $listing. This syntax allows

powerful processing capabilities within a

program.

printf, sprintf

printf(“%s lines here”, $counter)

if $counter is 42, we get

42 lines here

for the output

printf, sprintf

printf(“%c lines here”, $counter)

if $counter is 42, we get

* lines here

for the output, since 42 is the ASCII

value for “*”, and we’re printing a

character

printf, sprintf

Some additional string formatting…

%s – output length is length($var)

%10s – output length is absolutely 10

(right justified)

%10.20s – output length is min 10,

max 20

%-10.10s – output length is absolutely 10

(left justified)

Any padding is with space characters.

printf, sprintf

Some additional number formatting…

%d – output length is length($var)

%10d – output length is absolutely 10

(leading space padded)

%-10d – left justified, absolutely 10

(trailing space padded)

%-10.10d – right justified, absolutely 10

(leading zero padded)

printf, sprintf

Still more number formatting…

%f – output length is length($var)

%10.10f – guarantees 10 positions to the

right of the decimal (zero padded)

printf, sprintf

printf whatever outputs to the screen

printf, sprintf

printf whatever outputs to the screen

printf file whatever outputs to that file

Ex: printf file (“this is %s fun\n”, $much);

(print functions just like the above, as to

output destination.)

printf, sprintf

printf whatever outputs to the screen

printf file whatever outputs to that file

Ex: printf file (“this is %s fun\n”, $much);

(print functions just like the above, as to

output destination.)

sprintf is just like any printf, except that

its output always goes to a string

variable.

Ex: $var = sprintf(“this is %s fun\n”, $much);

ratiocheck.pl, what it does

When the ratio of sizes of certain files

related to a database exceeds a

threshold, it’s probably time to do an

index regen on that database.

ratiocheck.pl, what it does

When the ratio of sizes of certain files

related to a database exceeds a

threshold, it’s probably time to do an

index regen on that database.

This program computes these ratios for

several databases, each with its own

threshold, and flags those that are

candidates for index regeneration.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

set up some variables

two of these are templates for printing

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

In line 3 above, a file is slurped,

i.e., the entire file is read into an array

via the <> mechanism.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

This is a more typical use of the split

function. Here, $item is separated into

two pieces at the “|” character.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

We want to check every database in

alphabetical order. We are then calling the

checkit subroutine for each database.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

The system function executes its string as

an O.S. command. Here we are mailing a

file to two different people.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

This subroutine takes 1 argument.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

Remember our generic templates? Here

they are used as a format string for the

sprintf function.

$generic_path = "/m1/voyager/%s/data/";

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

The –s test returns a file’s size.

(There are several dozen different –x file tests.)

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

Compute the files’ size ratio with

sufficient decimal places.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

\n means new line, loosely equivalent to a CR,

or carriage return.

Since we want to print the “%” character, we

have to escape it with the “\” backslash.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

Here we have a hash reference…

we are checking if the ratio is greater than

the threshold for the current database.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

This is a busy printf statement…

the alert text gets a string, a character,

and a string embedded in it.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

The first argument is a string, which is

the output of the sprintf statement, which

outputs the threshold value for this

database.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

The second argument is a character. We

print the “%” character, whose ASCII

value is 37.

program dissection – ratiocheck.pl

The third argument is a string. In this

case, the string consists of 35 asterisks.

A string followed by “xN” will occur N times.

ratiocheck.pl, output

Here’s what the output looks like:

DBI stuff

What is it and why might I want it?

DBI is the DataBase Interface module for

Perl. You will also need the specific DBD

(DataBase Driver) module for Oracle.

This enables Perl to perform queries

against your Voyager database.

Both of these should already be on your

Voyager box.

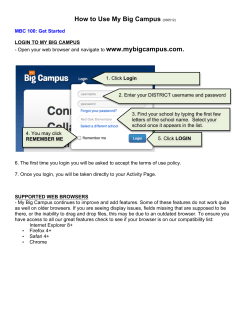

DBI stuff, how to

You need four things to connect to Voyager:

machine name your.machine.here.edu

username

your_username

password

your_password

SID

VGER (or LIBR)

DBI stuff, how to

$dbh is the handle for the database

$sth is the handle for the query

Create a query…then execute it.

NOTE: SQL from Access will most

likely NOT work here!

DBI stuff, how to

Get the data coming from your query.

DBI stuff, how to

Get the data coming from your query.

You’ll need a Perl variable for each column

returned in the query.

Commonly a list of variables is used; you

could also use an array.

DBI stuff, how to

Get the data coming from your query.

You’ll need a Perl variable for each column

returned in the query.

Commonly a list of variables is used; you

could also use an array.

Typically, you get your data in a while loop,

but you could have

$var = $sth->fetchrow_array;

when you know you’re getting a single value.

DBI stuff, how to

When you’re done with a query, you should

finish it. This becomes important when you

have multiple queries in succession.

You can have multiple queries open at the

same time. In that case, make the statement

handles unique…$sth2, or $sth_patron.

Finally, you can close your database

connection.

CPAN

Comprehensive Perl Archive Network

http://cpan.org

You name it and somebody has probably

written a Perl module for it, and you’ll find it

here.

There are also good Perl links here; look for

the Perl Bookmarks link.

CPAN

Installing modules

You need to be root for systemwide installation

on Unix systems.

On Windows machines, you’ll need to be

administrator.

You can install them “just for yourself” with a bit

of tweaking, and without needing root access.

If you’re not a techie, you’ll probably want to

find someone who is, to install modules.

Installing modules is beyond the scope of this

presentation.

Perl on your PC

You can get Perl for your PC from ActiveState.

They typically have two versions available; I

recommend the newer one. Get the MSI version.

Installation is easy and painless, but it may take

some time to complete.

A lot of modules are included with this

distribution; many additional modules are

available. Module installation is made easy via

the Perl Package Manager (PPM). Modules not

found this way will require manual installation,

details of which are beyond the scope of this

presentation.

Date and Time in Perl, basic

### "create" today's date

my ($sec, $min, $hour,

$day, $month, $year,

$wday, $yday, $isdst) = localtime;

This gets the date and time information

from the system.

Date and Time in Perl, basic

### "create" today's date

my ($sec, $min, $hour,

$day, $month, $year,

$wday, $yday, $isdst) = localtime;

my $today =

sprintf ("%4.4d.%2.2d.%2.2d",

$year+1900, $month+1, $day);

This puts today’s date in “Voyager”

format, 2006.04.26

Date and Time in Perl

The program, datemath.pl, is part of your

handout. The screenshot below shows its

output.

Regular expressions, matching

m/PATTERN/gi

If the m for matching is not there, it is

assumed.

The g modifier means to find globally, all

occurrences.

The i modifier means matching case

insensitive.

Modifiers are optional; others are

available.

Regular expressions, substituting

s/PATTERN/REPLACEWITH/gi

The s says that substitution is the intent.

The g modifier means to substitute

globally, all occurrences.

The i modifier means matching case

insensitive.

Modifiers are optional; others are

available.

Regular expressions, translating

tr/SEARCHFOR/REPLACEWITH/cd

The tr says that translation is the intent.

The c modifier means translate whatever

is not in SEARCHFOR.

The d modifier means to delete found but

unreplaced characters.

Modifiers are optional; others are

available.

Regular expressions

Look in the Perl book (see Resources) for

an explanation on how to use regular

expressions. You can look around

elsewhere, at Perl sites, and in other

books, for more information and

examples.

Looking at explained examples can be

very helpful in learning how to use

regular expressions.

(I’ve enclosed some I’ve found useful;

see Resources.)

Regular expressions

Very powerful mechanism.

Often hard to understand at first glance.

Can be rather obtuse and frustrating!

If one way doesn’t work, keep at it. Most

likely there is a way that works!

Resources

Learning Perl

Perl in a Nutshell

I use

these

two

a

lot

Highly recommended once

you’re experienced.

Programming Perl

Perl Cookbook

Perl Best Practices

Advanced Perl Programming

These are all O’Reilly books.

Resources

CPAN

http://cpan.org

Active State Perl

http://activestate.com/Products/Download/Download.plex?id=ActivePerl

The files listed below are available at

http://homepages.wmich.edu/~zimmer/files/eugm2006

datemath.pl

some program code for math with dates

snippet.grep

various regular expressions I’ve found useful

Plunging Into Perl.ppt

this presentation

Thanks for listening.

Questions?

roy.zimmer@wmich.edu

269.387.3885

Picture © 2005 by Roy Zimmer

© Copyright 2025