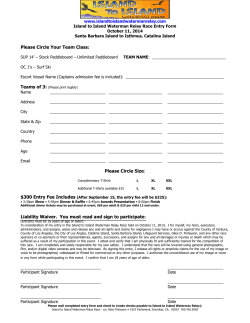

J R M E D I C A l