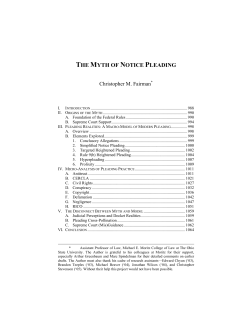

BAHR-HEBERT-FRANKLIN PARADOX: RESOLVING THE TWOMBLY AND ITS PROGENY CONSIDERATIONS FOR APPLYING