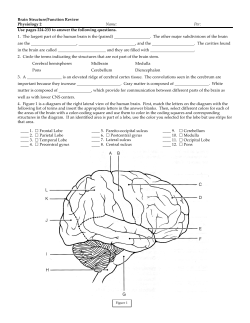

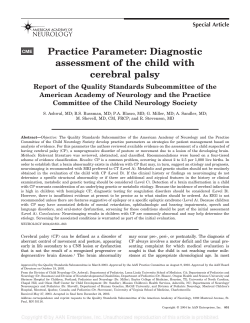

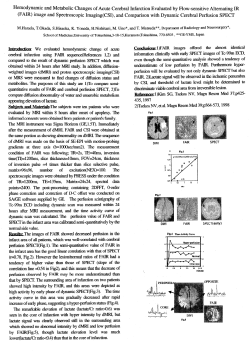

Information about cerebral palsy