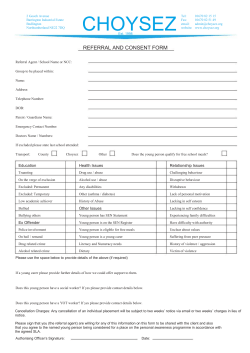

Information about behaviour