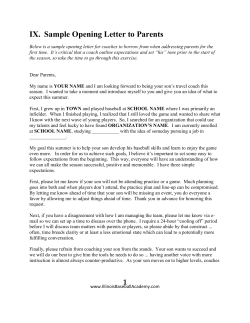

Wilson. Brutally Unfair Tactics Totally OK Now