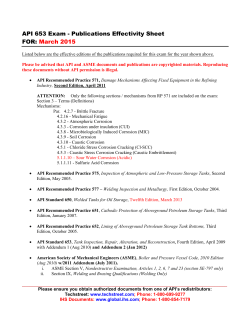

newsletter issue 28