12CHAPTER Money, Banking, and the Financial System

Money, Banking, and the Financial System 12 CHAPTER Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Money: A Definition To the layperson, the words income, credit, and wealth are synonyms for money. In each of the next three sentences, the word money is used incorrectly; the word in parentheses is the word an economist would use. 1. How much money (income) did you earn last year? 2. Most of her money (wealth) is tied up in real estate. 3. It sure is difficult to get money (credit) in today’s tight mortgage market. In economics, the words money, income, credit, and wealth are not synonyms. The most general definition of money is any good that is widely accepted for purposes of exchange (payment for goods and services) and the repayment of debt. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Three Functions of Money Money has three major functions; it is a: Medium of exchange Unit of account Store of value Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Medium of Exchange A medium of exchange is an object that is generally accepted in exchange for goods and services. In the absence of money, people would need to exchange goods and services directly, which is called barter. Barter requires a double coincidence of wants, which is rare, so barter is costly – it requires either much search, or lots of specialized middle-men. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Unit of Account In a money economy, a person doesn’t have to know the price of an apple in terms of oranges, pizzas, chickens, or potato chips, as in a barter economy. A person needs only to know the price in terms of money. A unit of account is an agreed measure for stating the prices of goods and services. This Table illustrates how money simplifies comparisons. Because all goods are denominated in money, determining relative prices is easy and quick. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Store of Value The store of value function is related to a good’s ability to maintain its value over time. This is the least exclusive function of money because other goods—for example, paintings, houses, and stamps—can store value too. At times, money has not maintained its value well, such as during high-inflationary periods. For the most part, though, money has served as a satisfactory store of value. This function allows us to accept payment in money for our productive efforts and to keep that money until we decide how we want to spend it. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? From a Barter to a Money Economy: The Origins of Money How did we move from a barter to a money economy? Did a king or queen issue an edict: “Let there be money”? Actually, money evolved in a much more natural, market-oriented manner. Making exchanges takes longer (on average) in a barter economy than in a money economy because the transaction costs are higher in a barter economy since it requires double coincidence of wants. In a barter economy, some goods are more readily accepted than others in exchange. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? From a Barter to a Money Economy: The Origins of Money Suppose that, of 10 goods A–J, good G is the most marketable (the most acceptable) of the 10. On average, good G is accepted 5 of every 10 times it is offered in an exchange, whereas the remaining goods are accepted, on average, only 2 of every 10 times. Given this difference, some individuals accept good G simply because of its relatively greater acceptability, even though they have no plans to consume it. The more people accept good G for its relatively greater acceptability, the greater its relative acceptability becomes, in turn causing more people to accept it. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? From a Barter to a Money Economy: The Origins of Money This is how money evolved. When good G’s acceptance evolves to the point that it is widely accepted for purposes of exchange, good G is money. Historically, goods that have evolved into money include gold, silver, copper, cattle, salt, cocoa beans, and shells. In many of the World War 2 prisoner of war (POW) camps, the cigarette was being used as money among the prisoners. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Money, Leisure, and Output Exchanges take less time in a money economy than in a barter economy because a double coincidence of wants is unnecessary: Everyone is willing to trade for money. The movement from a barter to a money economy therefore frees up some of the transaction time, which people can use in other ways. Some will use them to work, others will use them for leisure, and still others will divide the available time between work and leisure. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Money, Leisure, and Output Thus, a money economy is likely to have both more output (because of the increased production) and more leisure time than a barter economy. In other words, a money economy is likely to be richer in both goods and leisure than a barter economy. A person’s standard of living depends, to a degree, on the number and quality of goods consumed and on the amount of leisure consumed. We would expect the average person’s standard of living to be higher in a money economy than in a barter economy. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Finding Economics with William Shakespeare in London (1595) It is 1595, and William Shakespeare is sitting at a desk writing the Prologue to Romeo and Juliet. Where is the economics? More specifically, what is the connection between Shakespeare’s writing a play and the emergence of money out of a barter economy? For Shakespeare, living in a barter economy would mean writing plays all day and then going out and trying to trade what he had written that day for apples, oranges, chickens, and bread. Would the baker trade two loaves of bread for two pages of Romeo and Juliet? Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Finding Economics with William Shakespeare in London (1595) Had Shakespeare lived in a barter economy, he would have soon learned that he did not have a double coincidence of wants with many people and that if he were going to eat and be housed, he would need to spend time baking bread, raising chickens, and building a shelter instead of thinking about Romeo and Juliet. In a barter economy, trade is difficult; so people produce for themselves. In a money economy, trade is easy, and so individuals produce one thing, sell it for money, and then buy what they want with the money. A William Shakespeare who lived in a barter economy no doubt spent his days very differently from the William Shakespeare who lived in England in the sixteenth century. Put bluntly: Without money, the world might never have enjoyed Romeo and Juliet. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Components of Money Money consists of Currency Deposits at banks and other depository institutions Currency is the notes and coins held by households and firms. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Official Measures of Money The two main official measures of money are M1 and M2. M1 consists of currency and traveler’s checks and checking deposits owned by individuals and businesses. M2 consists of M1 plus time, saving deposits, money market mutual funds, and other deposits. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? The figure illustrates the composition of M1… and M2. It also shows the relative magnitudes of the components. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Are M1 and M2 Really Money? All the items in M1 are means of payment. They are money. Some saving deposits in M2 are not means of payments— they are called liquid assets. Liquidity of an asset measures how quickly the asset can be converted into cash (a means of payment) with little/no loss of value. Money: What Is It and How Did It Come to Be? Deposits are Money but Checks Are Not In defining money, we include, along with currency, deposits at banks and other depository institutions. But we do not count the checks that people write as money. A check is an instruction to a bank to transfer money. Credit Cards Are Not Money Credit cards are not money. A credit card enables the holder to obtain a loan, but it must be repaid with money. How Banking Developed Just as money evolved, so did banking. The Early Bankers Our money today is easy to carry and transport, but it was not always so portable. For example, when money consisted principally of gold coins, carrying it about was neither easy nor safe. Gold was not only inconvenient for customers to carry, but it was also inconvenient for merchants to accept - gold is heavy. Gold is unsafe to carry around - can easily draw the attention of thieves. Storing gold at home can also be risky. How Banking Developed The Early Bankers Most individuals therefore turned to their local goldsmiths for help because they had safe storage facilities. Goldsmiths were thus the first bankers. They took in other people’s gold and stored it for them. To acknowledge that they held deposited gold, goldsmiths issued receipts, called warehouse receipts, to their customers. Once people’s confidence in the receipts was established, they used the receipts to make payments instead of using the gold itself. In time, the paper warehouse receipts circulated as money. How Banking Developed The Early Bankers At this stage of banking, warehouse receipts were fully backed by gold; they simply represented gold in storage. Goldsmiths later began to recognize that, on an average day, few people redeemed their receipts for gold. Many individuals traded the receipts for goods and seldom requested the gold itself. In short, the receipts had become money, widely accepted for purposes of exchange. Sensing opportunity, goldsmiths began to lend some of the stored gold, realizing that they could earn interest on the loans without defaulting on their pledge to redeem the warehouse receipts when presented. How Banking Developed The Early Bankers In most cases, however, the gold borrowers also preferred warehouse receipts to the actual gold. Thus the warehouse receipts came to represent a greater amount of gold than was actually on deposit. Consequently, the money supply increased, now measured in terms of gold and the paper warehouse receipts issued by the Goldsmith/bankers. Thus fractional reserve banking had begun. In a fractional reserve system, banks create money by holding on reserve only a fraction of the money deposited with them and lending the remainder. Our modern-day banking operates within such a system. Direct and Indirect Finance Lenders can get together with borrowers directly or indirectly; that is, there are two types of finance: direct and indirect. Direct finance In direct finance, the lenders and borrowers come together in a market setting, such as the bond market. In the bond market, people who want to borrow funds issue bonds. For example, company A might issue a bond that promises to pay an interest rate of 10 percent annually for the next 10 years. A person with funds to lend might then buy that bond for a particular price. The buying and selling in a bond market are simply lending and borrowing. The buyer of the bond is the lender, and the seller of the bond is the borrower. Direct and Indirect Finance Indirect finance In indirect finance, lenders and borrowers go through a financial intermediary, which takes in funds from people who want to save and then lends the funds to people who want to borrow. For example, a commercial bank is a financial intermediary, doing business with both savers and borrowers. Through one door the savers come in, looking for a place to deposit their funds and earn regular interest payments. Through another door come the borrowers, seeking loans on which they will pay interest. The bank, or the financial intermediary, ends up channeling the saved funds to borrowers. Depository Institutions A depository institution is a firm that accepts deposits from households and firms and uses the deposits to make loans to other households and firms. The deposits of three types of depository institution are part of the nation’s money: Commercial banks Thrift institutions Money market mutual funds Depository Institutions Commercial Banks A commercial bank is a private firm that is licensed to receive deposits and make loans. A commercial bank’s balance sheet summarizes its business and lists the bank’s assets, liabilities, and net worth. The objective of a commercial bank is to maximize the net worth of its stockholders, by making profits. Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard Problems When it comes to lending and borrowing, both adverse selection and moral hazards can arise. Both are the result of asymmetric information. Asymmetric information relates to one side of a transaction having information that the other side does not have. Suppose Rahima is going to sell her house. As the seller of the house, she has more information about the house than potential buyers. Rahima knows whether the house has plumbing problems, cracks in the foundation, and so on. Potential buyers do not. Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard Problems The effect of asymmetric information can be either an adverse selection problem or a moral hazard problem. The adverse selection problem (hidden type) occurs before the loan is made, and the moral hazard problem (hidden action) occurs afterward. Before the loan is made An adverse selection problem occurs when the parties on one side of the market, having information not known to others, self-select in a way that adversely affects the parties on the other side of the market. Think of it this way: Two people want a loan. One person is a good credit risk, and the other is a bad credit risk. The person who is the bad credit risk is the person more likely to ask for the loan. Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard Problems Before the loan is made Suppose two people, Selim and Salina, want to borrow Tk. 100,000 , and Malek has Tk. 100,000 to lend. Salina wants to borrow the Tk. 100,000 to buy a piece of equipment for her small business. She plans to pay back the loan, and she takes her loan commitments very seriously. She is the Good type. Selim wants to borrow the Tk. 100,000 so that he can gamble. He will pay back the loan only if he wins big gambling. He is not the type of person who takes his loan commitments seriously. He is the Bad type. Who is more likely to ask Malek for the loan, Selim or Salina? Selim is because he knows that he will pay back the loan only if he wins big in gambling; he sees a loan as essentially “free money.” Heads, Selim wins; tails, Malek loses! Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard Problems Before the loan is made If Malek can’t separate the good types from the bad types, what can he do? He might just decide not to give a loan to anyone. In other words, his inability to solve the adverse selection problem may be enough for him to decide not to lend to anyone. At this point, a financial intermediary can help. A bank does not require Malek to worry about who will and who will not pay back a loan. Malek needs simply to turn over his saved funds to the bank, in return for the bank’s promise to pay him say a 5 percent interest rate per year. Then, the bank takes on the responsibility of trying to separate the good types from the bad ones. The bank will run a credit check on everyone; the bank will collect information on who has a job and who doesn’t; the bank will ask the borrower to put up some collateral on the loan; and so on. In other words, the bank’s job is to solve the adverse selection problem. Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard Problems After the loan is made The moral hazard problem exists when one party to a transaction changes his or her behavior in a way that is hidden from and costly to the other party. Suppose you want to lend some saved funds. You give Selim a Tk. 100,000 loan because he promised you that he was going to use the funds to help him get through university. Instead, once Selim receives the money, he decides to use the funds to buy some clothes and take a vacation to Thailand. Because of such potential moral hazard problems, you might decide to cut back on granting loans. You want to protect yourself from borrowers who do things that are costly to you. Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard Problems After the loan is made Again, a financial intermediary has a role to play. A financial intermediary, such as a bank, might try to solve the moral hazard problem by specifying that a loan can only be used for a particular purpose (e.g., paying for university). It might require the borrower to provide regular information on and evidence of how the borrowed funds are being used, giving out the loan in installments (Tk. 10,000 this month, Tk. 10,000 next month), and so on. Financial Regulation There are four main balance sheet rules: Capital requirements Reserve requirements Deposit rules Lending rules How Banks Create Money To achieve its objective, a bank makes (risky) loans at an interest rate higher than that paid on deposits. But the banks must balance profit and prudence; loans generate profit, but depositors must be able to obtain their funds when they want them. Banks’ funds come from their assets, which we divide into two important parts: reserves and loans. Reserves are the cash in a bank’s vault and the bank’s deposits at Federal Reserve Banks. Bank assets also include buildings and equipment, liquid assets, investment securities, and loans. How Banks Create Money Reserves: Actual and Required The fraction of a bank’s total deposits held as reserves is the reserve ratio. The required reserve ratio is the fraction that banks are required, by regulation, to keep as reserves. Required reserves are the total amount of reserves that banks are required to keep. Excess reserves equal actual reserves minus required reserves. How Banks Create Money Creating Deposits by Making Loans in a One-Bank Economy When a bank receives a deposit of currency, its reserves increase by the amount deposited, but its required reserves increase by only a fraction (determined by the required reserve ratio) of the amount deposited. The bank has excess reserves, which it loans. These loans can only end up as deposits in our one and only bank, where they boost deposits without changing total reserves, which creates money. How Banks Create Money This Figure illustrates how one bank create money by making loans. How Banks Create Money The Deposit Multiplier The deposit multiplier is the amount by which an increase in bank reserves is multiplied to calculate the increase in bank deposits. The deposit multiplier = 1/Required reserve ratio. How Banks Create Money Creating Deposits by Making Loans with Many Banks With many banks, one bank lending out its excess reserves cannot expect its deposits to increase by the full amount loaned; some of the loaned reserves end up in other banks. But then the other banks have excess reserves, which they loan. Ultimately, the effect in the banking system is the same as if there was only one bank, so long as all loans are deposited in banks. How Banks Create Money This Figure illustrates money creation with many banks.

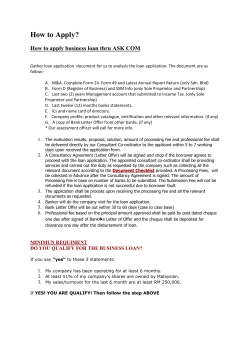

© Copyright 2025