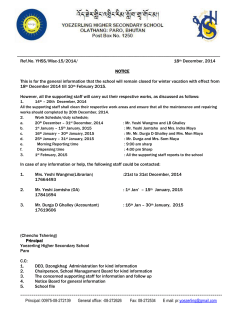

as a PDF