“SUPPORT FOR THE FURTHER APPROXIMATION OF CROATIAN LEGISLATION WITH THE ENVIRONMENTAL ACQUIS”

“SUPPORT FOR THE FURTHER

APPROXIMATION OF CROATIAN LEGISLATION

WITH THE ENVIRONMENTAL ACQUIS”

REPUBLIC OF CROATIA

The European Union CARDS 2004 Programme for Croatia

Contracting Authority: The Central Finance and Contracting Agency, Republic

of Croatia

Beneficiary: Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and

Construction, Republic of Croatia

ProjectCycleManagement

ManualforEndRecipientsofEUFundsinthe

EnvironmentalSector

May 2009

Document Control Sheet

Issue No: A

Sign-Off

Name

Date: May 2009

Originator

Checker

NPC - MEPPPC

Reviewer

Michael Betts

Tim Young

Vlatka Lucijaniü-Justiü

Andrzej Gula

Tim Young

Peter Nesteruk

Michael Betts

Signature

Date

Name

Signature

Date

Name

Signature

Date

CFCA – Approver

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1

1.

INSTRUMENT FOR PRE-ACCESSION ASSISTANCE (IPA)

2

1.1

Accession Partnership & Strategic Development Framework

2

1.2

General Overview of IPA

3

1.3

IPA Programming & Documentation

4

1.4

IPA Management and Control

1.4.1 Key IPA Players

1.4.2 IPA Institutional / Operating Structure

7

7

8

1.5

IPA and the Structural / Cohesion Funds

12

2.

PROJECT CYCLE MANAGEMENT (PCM)

14

2.1

Project Cycle Framework

14

2.2

PCM and the Logical Framework Approach

16

2.3

Key Documents & Responsibilities

18

2.4

The Financing Decision

18

3.

IPA APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS

20

3.1

The Application Process

20

3.2

General Requirements

21

3.3

Technical Requirements

22

3.4

Financial and Economic Requirements

22

3.5

Institutional Requirements

24

3.6

Environmental Requirements

24

3.7

Public Consultation and Participation

26

3.8

Special Criteria for Waste Management Projects

26

3.9

Some Lessons Learned from the IPA Application Process in Croatia

28

4.

PROJECT IDENTIFICATION & DEFINITION

29

4.1

Project Identification

29

4.2

Policy & Legal Analysis

30

4.3

Stakeholder Analysis

31

4.4

Problem Analysis

32

4.5

Objectives Analysis

33

4.6

Strategy Development

33

4.7

Project Definition & Terms of Reference

35

5.

PROJECT FEASIBILITY & PREPARATION

37

5.1

Demand Forecasts

37

5.2

Options Assessment

5.2.1 Technical Assessment

5.2.2 Environmental Assessment

5.2.3 Institutional Assessment

38

38

40

40

5.3

Financial Analysis

5.3.1 Methodological and Modelling Assumptions for Financial Analysis

5.3.2 Investment Costs

5.3.3 Operating and Maintenance Costs

5.3.4 Revenues from Sale of By-Products

5.3.5 Affordability Analysis and Tariff Determination

5.3.6 Calculation of the Funding Gap – Determination of the EU Grant

5.3.7 Financing Plan

5.3.8 Financial Viability Analysis, and Calculation of NPV and IRR

43

45

48

50

50

50

52

54

55

5.4

Economic Analysis (ENPV and ERR)

57

5.5

Sensitivity and Risk Analysis

5.5.1 Sensitivity Analysis

5.5.2 Risk Analysis

59

59

61

5.6

Overall Assessment

62

5.7

Implementation Plan

63

6.

PROJECT PROCUREMENT

65

6.1

Key Principles of Public Procurement

65

6.2

Procurement & the Practical Guide

65

6.3

Contract Types & Conditions

6.3.1 Types of Contract

6.3.2 Contract Conditions

66

66

67

6.4

Contract Tendering and Award

6.4.1 Participation and Eligibility Criteria

6.4.2 Procurement Procedures

6.4.3 Selection and Award

68

68

69

71

6.5

Tender Dossiers

72

7.

PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION, MONITORING & REPORTING

73

7.1

Purpose

73

7.2

Implementation Tasks

73

7.3

Contract & Performance Management

73

7.4

Role of the FIDIC Supervising Engineer

75

7.5

Project Monitoring, Evaluation & Reporting

7.5.1 Project Monitoring & Evaluation

7.5.2 Project Reporting

75

77

78

ANNEX A: ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES FOR PROJECT IDENTIFICATION & FORMULATION

80

ANNEX B: CASE STUDY

89

ANNEX C: PREPARING TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECTS

FINANCED BY THE EC

109

ANNEX D: OTHER SOURCES OF INVESTMENT FUNDING

114

ANNEX E: CONTENTS OF TENDER DOSSIERS

117

ANNEX F: INDICATIVE CHECK-LIST OF CONTRACT MANAGEMENT ISSUES FOR WASTE

PROJECTS

121

ANNEX G: RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE SUPERVISING ENGINEER IN RELATION TO WORKS

CONTRACTS

124

ANNEX H: GENERAL CHECK-LIST FOR A COHESION FUND APPLICATION

127

ANNEX I: CHECK-LIST FOR THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ASPECTS OF A CF APPLICATION

139

ANNEX J: ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS

144

ANNEX K: GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS

147

ANNEX L: FURTHER REFERENCES

158

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

INTRODUCTION

This Manual on Project Cycle Management for End Recipients of EU Funds in the

Environmental Sector (hereafter referred to as "the Manual") has been prepared as a component of

the Technical Assistance project "Support for the Further Approximation of Croatian Legislation with

the Environmental Acquis", a project funded under the European Union CARDS 2004 Programme for

Croatia (Project No: CARDS 2004 2004-0101-0500-010101). The principal beneficiary of the Project

was the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and Construction of the Republic of

Croatia (MEPPPC).

The Project provided support to the Ministry of Environmental Protection Physical Planning and

Construction (MEPPPC) in order to increase Croatia’s capacity to meet EU environmental standards.

In particular, one of the results to be achieved by the Project was to "increase Croatia's national

absorption capacity for environmental investment projects, particularly in relation to the upcoming IPA

(Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance) funding for waste management."

The Manual is therefore aimed at providing prospective End Recipients of EU funds in the

environmental sector (development agencies; municipalities; municipal enterprises) with a basic

knowledge and understanding of the key requirements and practical considerations involved in

identifying, planning, preparing and implementing major investment projects in the waste

management sector, taking into account the requirements of EU and national policies and legislation

on waste management, IPA rules and procedures, and Croatia's National Waste Management

Strategy and National Waste Management Plan. The Manual is further aimed at assisting Croatia to

prepare for absorbing the much larger funds that will become available following Croatia's accession

to the European Union.

At the request of the MEPPPC, the Manual focuses primarily on the pre-financing stages of the

project cycle, i.e. the stages leading up to the point where a proposed investment project is ready for

submission to the European Commission for potential co-financing. The Manual places particular

emphasis on the financial and economic analysis of projects as these aspects are especially

important for preparing a successful application for EU grant support. It is also designed to assist

applicants in meeting the criteria set out in the application form for IPA funding (and eventually for

financing from the Cohesion Fund) and ensuring that a proposed project complies with the

requirements set out in the respective regulations.

The Manual is structured as follows:

Chapter 1 provides an introduction to the principles of IPA, and the IPA structure, strategy,

objectives, programming and documentation in Croatia.

Chapter 2 presents an overview of Project Cycle Management (PCM) for projects co-financed by

the EU.

Chapter 3 explains the IPA application process and associated requirements, with particular

reference to waste management investment projects.

Chapter 4 describes the key steps involved in identifying and defining an environmental

investment project for potential EU funding.

Chapter 5 describes and explains the steps and essential requirements for undertaking a detailed

project feasibility study, and preparing a project for potential EU funding.

Chapter 6 presents a summary of the project procurement process for investment projects cofinanced by the EU, in particular the various contract types and conditions, tender types and

requirements and preparation of tender dossiers.

Chapter 7 provides an overview of the purpose and essential requirements of project

implementation, monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

Further information and guidance is presented in a series of annexes, covering notably analytical

techniques for project identification and formulation, a case study based on an actual application for

co-financing a waste management project from the EU Cohesion Fund, and the key requirements for

preparing Terms of Reference for later stages of a project.

1

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

1.

INSTRUMENT FOR PRE-ACCESSION ASSISTANCE (IPA)

1.1

Accession Partnership & Strategic Development Framework

At the broadest level, relations between Croatia and the European Union (EU) are governed

by the Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) which is in force since February 2005.

The SAA provides a legal framework for the political dialogue, regional cooperation, the

establishment of the free trade area, alignment to Community law ("acquis communautaire")

in certain areas, cooperation on the Community policies, and the use of EU financial

assistance.

In April 2004, the Council of the European Union adopted the European Partnership with

Croatia, which was updated to the Accession Partnership (AP) in February 2006 in order to

reflect Croatia’s new status as a candidate for EU membership. The Accession Partnership

describes the priorities for each sector in transposing the acquis, the priorities for aid provided

by the European Community, in particular the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA),

and the conditions for grant financing. It is intended to assist Croatia’s authorities in their

efforts to comply with the accession criteria and set out in detail the priorities for preparing for

accession, in particular implementing the Community acquis.

The AP is a flexible instrument, designed to adapt to the progress already made by Croatia

and take account of what still remains to be achieved. In this regard, the various priorities

identified by the AP are defined according to the European Commission's opinion on Croatia's

Application for Membership. The AP is reviewed and revised as necessary in light of the

European Commission’s regular reports on Croatia’s progress in relation to accession.

1

According to the most recently updated AP , the key priorities in the area of environment are

to:

Continue work on transposition and implementation of the EU acquis, with particular

emphasis on waste management, water quality, air quality, nature protection and

integrated pollution prevention and control.

Adopt and implement a comprehensive plan for putting in place the necessary

administrative capacity and required financial resources to implement the environment

acquis.

Increase investments in environmental infrastructure, with particular emphasis on waste

water collection and treatment, drinking water supply and waste management.

Start implementing the Kyoto Protocol.

Ensure integration of environmental protection requirements into the definition and

implementation of other sectoral policies and promote sustainable development.

From the perspective of the Republic of Croatia, the overarching strategy document is the

Strategic Development Framework (SDF) 2 . The SDF defines Croatia’s national economic

goals and the instruments for their implementation in the period between 2006 and 2013, with

the overall aim to achieve prosperity through the development of both a competitive economy

and social cohesion. In the area of environment and sustainable development, the SDF notes

that:

"Waste management and the remediation of existing effects arising from the inadequate

management of waste are of particular importance in the achievement of sustainable

development. It is therefore necessary to establish an integrated system for waste

management, to remediate and close existing and “wild” landfills, and establish centres for

waste management".

1

A copy of the most recent Accession Partnership may be downloaded from

http://www.delhrv.ec.europa.eu/en/static/view/id/14

2

A copy of the Strategic Development Framework may be downloaded from http://www.strategija.hr

2

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

1.2

General Overview of IPA

The Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) was established in July 2006 (Council

Regulation No. 1085 / 2006) 3 . IPA is the European Union's financial instrument for

supporting the pre-accession process during the period 2007-2013, and offers targeted

assistance to countries aspiring to join the EU on the basis of the lessons learnt from previous

external assistance and pre-accession instruments. The aim of IPA is therefore to enhance

the efficiency and coherence of EU aid by means of a single framework, which incorporates

the previous pre-accession and stabilisation and association assistance to candidate

countries and potential candidate countries. IPA replaces the preceding PHARE, ISPA,

SAPARD and CARDS pre-accession instruments.

The IPA beneficiary countries are divided into two categories, depending on their status as

either candidate countries under the accession process or potential candidate countries under

the stabilisation and association process, namely:

Candidate countries (Annex I to the Regulation): Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic

of Macedonia, Turkey;

Potential candidate countries (Annex II to the Regulation): Albania, Bosnia and

Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia including Kosovo as defined by the United Nations

Security Council Resolution 1244.

The annexes to the Regulation will be amended as and when changes in the status of the

countries occur.

IPA aims to support the candidate countries in:

Policy reform and development.

Adopting EU policies, standards and legislation.

Preparing to implement and manage the Community’s Cohesion Policy effectively.

Preparing for programming, implementation and management of Structural and Cohesion

Funds.

Candidate countries are therefore prepared for full implementation of the acquis at the time of

accession, while potential candidate countries are led to progressively align themselves with

the acquis.

IPA is made up of five components, each covering priorities defined according to the needs of

the beneficiary countries. Two components concern all beneficiary countries:

I.

Support for transition and institution-building, aimed at financing capacity-building

and institution-building;

II. Cross-border cooperation, aimed at supporting the beneficiary countries in the area of

cross-border cooperation between themselves, with the Member States or within the

framework of cross-border or inter-regional actions.

The other three components are aimed at candidate countries only:

III. Regional development, aimed at supporting candidate countries' preparations for the

implementation of the Community's cohesion policy, and in particular for the European

Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund;

IV. Human resources development, which concerns preparation for cohesion policy and

the European Social Fund;

V. Rural development, which concerns preparation for the common agricultural policy and

related policies and for the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD).

The total IPA budget, for all candidate and potential candidate countries, for the period from

2007 to 2013 is €11,468 million. The nominal IPA allocations for Croatia for the period 2007 to

2011 are shown in Table 1.

3

A copy of the Regulation may be downloaded from http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/funds/ipa/index_en.htm

3

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

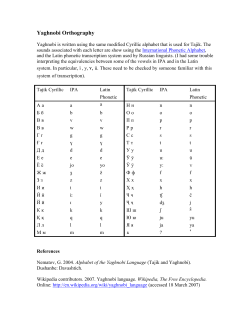

Table 1: Nominal IPA Allocations for Croatia for the Period 2007 to 2011 (€ million)

Component

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

49.6

45.4

45.6

39.5

40.0

9.7

14.7

15.9

16.2

16.5

III. Regional Development

45.0

47.6

49.7

56.8

58.2

IV. Human Resources Development

11.4

12.7

14.2

15.7

16.0

V. Rural Development

25.5

25.6

25.8

26.0

26.5

141.2

146.0

151.2

154.2

157.2

I.

Transition Assistance & Institution

Building

II. Cross-border cooperation

Totals

The Community contribution under IPA shall not exceed the ceiling of 75 % of the eligible

expenditure at the level at the Priority Axis (see section 1.3 below). In exceptional and duly

justified cases, with regard to the scope of the Priority Axis, this ceiling may reach 85 % 4 .

1.3

IPA Programming & Documentation

The main principles establishing the IPA programme are contained in Commission Regulation

No. 1085 / 2006 (IPA regulation). Detailed rules and procedures for planning, programming

and implementing IPA are contained in Commission Regulation 718 / 2007 (IPA implementing

regulation) 5 . In the context of IPA, programming may be defined as the preparation of a set

of financial, organisational and human interventions that are mobilised to achieve an objective

or set of objectives in a given period. A programme has a specified budget, and a coherent

set of programme objectives are also specified at the outset.

By adopting a programming approach, the intention is to prepare candidate countries for the

management of the Structural and Cohesion Funds upon accession to the EU. Programming

has been a key characteristic of the EU’s Structural Policies since they were reformed in 1988

and is the distinctive difference between IPA Components III and IV (which reflect Structural

Policies practice) and earlier forms of EU assistance to Croatia. An overview of the

programming framework for IPA Component III (Regional Development) is presented in

Figure 1.

The policies and objectives pursued with the assistance of IPA should be consistent with the

amount of assistance that is available and with wider relevant policies. Therefore, the starting

point for programming is to take account of this context. The European Commission prepares

a Multi-annual Indicative Financial Framework (MIFF). The MIFF is based on a rolling threeyear programming cycle. Under normal circumstances, the MIFF for the years N, N+1 and

N+2 is presented in the last quarter of the year N-2 as part of the enlargement package,

representing a proposed financial translation of the political priorities set out within the

package itself. Based on the MIFF, a Multi-annual Indicative Planning Document (MIPD) is

prepared by the Commission for each country in the year N-1. The MIPD sets out the

strategic context within which the MIFF is to be programmed. It provides the Commission's

view of the major areas of intervention and main priorities that the beneficiary country is

expected to articulate in detail in the programming documents.

4

Article 149 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 718/2007 of June 2007 Implementing Council Regulation (EC)

No 1085/2006 Establishing an Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA).

5

A copy of the Regulation may be downloaded from http://www.strategija.hr

4

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Figure 1: Programming Framework for IPA Component III

Coherence with Croatia’s own view of its needs, challenges and priorities must be assured

through consultations with the national authorities. The MIPD, like the MIFF, covers a threeyear rolling period with annual reviews and is submitted annually to the IPA Committee for an

opinion.

The programming approach to IPA Components III & IV entails the elaboration of a set of

programming documents: the Strategic Coherence Framework (SCF), which serves as the

overarching reference document for the use of IPA Components III and IV in Croatia, and four

Operational Programmes (OPs), one each for Transport, Environment and Regional

Competitiveness under Component III and one for Human Resource Development under

Component IV.

Taking account of the EU and national policy and financial contexts, the SCF is elaborated for

the full IPA programming period (2007-2013). The OPs are subsequently finalised for three

year periods (in the first instance 2007-2009) and are either to be a) reviewed and extended

by one further year annually up to 2013 or by the year of Croatia’s accession to the Union

(whichever comes first), or b) succeeded by a second generation of OPs for the 2010-2013

period.

The Environmental Protection Operational Programme (EPOP) is intended to support

operations related to waste management, water supply, urban wastewater management and

rehabilitation of contaminated sites and land. 6 As illustrated in Figure 2, the EPOP is divided

into three so-called Priority Axes covering respectively the waste sector (Priority Axis 1),

water sector (Priority Axis 2) and technical assistance (Priority Axis 3).

6

The EPOP and other documents referred to in this section may all be downloaded from http://www.strategija.hr

5

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Figure 2: Overview of the Environmental Protection Operational Programme (EPOP) 2007-2009

The aim of Priority Axis 1 is to support the establishment of an integrated waste management

system by developing waste management infrastructure, notably the development of Waste

Management Centres (WMCs) at County and Regional levels. Activities under this Priority

Axis are designed to improve waste management and assist Croatia in meeting its obligations

related to implementation of the EU environmental acquis governing the management of

waste, in particular:

The Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC)

The Waste Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC)

The objectives of this Priority Axis are inter alia to:

Develop waste management infrastructure with a focus on the construction of regional /

county waste management centres (separation of waste by categories, treatment with the

aim to reduce biological component of waste, landfill for final disposal of residues) which

will replace existing landfills;

Remediate and close sites highly polluted by waste; and

Prepare technical documentation (i.e. feasibility studies, environmental impact

assessments, financial and economic analyses, cost-benefit analyses, affordability

studies, preliminary designs, tender documents etc.) that will support a pipeline of

projects for waste management investments.

Besides the transposition and enactment of the relevant EU legislation, the national policy

framework and foundation for efforts aimed at achieving a more sustainable system of waste

management in Croatia is provided by the:

National Environmental Strategy (2002)

National Environmental Action Plan (2002)

National Waste Management Strategy 2007 – 2025 (2005)

National Waste Management Plan 2007 – 2015 (2007)

The operations (major projects) that will be co-financed under Priority Axis 1 will be selected

from the indicative major project list provided in the EPOP.

A major project comprises a series of works, activities or services which is intended, in itself,

to accomplish a definite and indivisible task of a precise economic or technical nature, which

has clearly identified goals and whose total cost exceeds €10 million. For the waste

management sector, the maximum rate of IPA co-financing is set at 75% of eligible project

costs.

6

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

1.4

IPA Management and Control

1.4.1 Key IPA Players

In accordance with the provisions of Commission Regulation No. 718 / 2007, the following

individuals / bodies have been designated / established for the management and control of

IPA:

National IPA Co-ordinator (NIPAC)

Strategic Co-ordinator for the regional development and human resources development

components (SC)

Competent Accrediting Officer (CAO)

National Authorising Officer (NAO)

National Fund (NF)

Operating Structure by IPA component / programme (OS)

Head of Operating Structure (HOS)

Audit Authority (AA)

An explanation of the roles and main responsibilities of the above-mentioned key IPA players

may be found in Annex K.

The main players responsible for managing the implementation of Priority Axis 1 are:

Operational Programme level: Ministry of Environment Protection, Physical Planning and

Construction (MEPPPC).

Priority / Measure level: MEPPPC Directorate for European Union.

Project level: Environment Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund (EPEEF), which serves

as the Implementing Body / Contracting Authority for projects in the waste management

sector.

The contact details for the MEPPPC and EPEEF are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Contact Details for the MEPPPC and EPEEF

Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and Construction:

Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and Construction

Directorate for European Union

Ulica Republike Austrije 14,

10 000 Zagreb

dr. Nikola Ružinski, State Secretary (Head of Operating Structure)

Ms. Mira Mediü, MSc, Director of Directorate

Ms. Vlatka Lucijaniü-Justiü, MSc, Head of Department for EU Programmes for Infrastructure

Development

Tel: (01) 3717-165

Fax: (01) 3717-122

E-mail: vlatka.lucijanic-justic@mzopu.hr

Website: www.mzopu.hr

Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund:

Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund

Ksaver 208,

10 000 Zagreb

Mr. Vinko Mladineo, Director

Ms. Andreja Neral Lamza, Head of Department for Preparation and Implementation of Projects CoFinanced by EU

Tel: + 385 1 53 91800

Fax: + 385 1 53 91840

E-mail: kontakt@fzoeu.hr

Website: www.fzoeu.hr

7

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

1.4.2 IPA Institutional / Operating Structure

For each IPA component or programme, an Operating Structure is established to deal with

the management and implementation of assistance under the IPA Regulation in accordance

with the principle of sound financial management. The Operating Structure for IPA

Component III b – Environment – is composed of the following bodies:

Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and Construction (MEPPPC),

performing the functions of the Body Responsible for the EPOP (OP) and of the Body

Responsible for the Priority / Measure (Priority Axes 1 and 3).

Ministry of Regional Development, Forestry and Water Management, performing the

function of the Body Responsible for Priority / Measure (Priority Axis 2).

Croatian Waters, performing the function of Implementing Body for Priority Axis 2.

Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund (EPEEF), performing the function

of Implementing Body for Priority Axis 1.

The Central Finance and Contracting Agency for EU Programmes and Projects (CFCA),

performing the function of Implementing Body for Priority Axis 3.

An overview of the institutional / operating structure for the EPOP is shown in Figure 3. All

the bodies within the Operating Structure are ultimately accountable to the MEPPPC which

has overall responsibility for management of the EPOP, and for the execution of their specific

tasks in relation to this Programme. The State Secretary for Environmental Protection of the

MEPPPC acts as the Head of the Operating Structure.

With respect to the MEPPPC's function as the Body responsible for the Priority / Measure,

notably measures falling within Priority Axis 1, the MEPPPC is responsible for / executes the

following tasks:

preparation of the sections/revision of the Operational Programme within their sectoral

area of responsibility; drafting priorities and measures for annual or multi annual

programmes;

supporting the Body Responsible for OP in the identification, for each measure, of the

intended final beneficiaries, the expected selection modalities and possible related

specific selection criteria (Article 155 of IPA Implementing Regulation);

supporting the Body Responsible for OP in the identification, selection and appraisal of

major projects under the OP which will be submitted to the Commission for approval,

within their sectoral area of responsibility;

supporting the Body Responsible for OP in the identification, selection and appraisal of

operations which are not major projects, and which will be implemented by the final

beneficiaries which are national public bodies;

ensuring that operations within their sectoral area of responsibilities are selected for

funding and approved in accordance with criteria applicable to the Operational

programme ;

preparation of monitoring data/reports on the implementation within their sectoral area of

responsibility;

contributing to the preparation of sectoral annual and final implementation reports for the

Sectoral Monitoring Committee on the progress achieved towards the fulfilment of the

objectives of priorities and measures;

supervision of technical implementation of projects in which The Body responsible for the

Priority/Measure is a beneficiary;

conducting a sample check of the tender documentation elaborated by the Implementing

Body, prior to its submission to the ECD for ex-ante approval;

performing institutional on-the-spot check;

preparing Technical Specifications/ToRs in case the Body Responsible for the

Priority/Measure is beneficiary;

8

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

preparing Guidelines for Applicants for projects which shall be selected through Calls for

Proposals, if applicable;

proposing members of the Evaluation Committee;

participation in Project Steering Committees, if applicable;

issuing of approvals for delivered products/ project results (e.g. equipment, reports), if

applicable;

organising the publication of the information (names and addresses) of final beneficiaries

and end recipients, the names of the operations and the amount of funding allocated to

the operations;

administrative check and approval of requests for payment issued by the Implementing

Body;

submission of requests for payment and all supporting documents to the NF;

ensuring that co-financing funds, within their sectoral area of responsibility, are planned

and reserved in the State Budget;

transfer of national co-financing funds from the Treasury account (the State Budget) to

the MF-IB IPA account;

preparation and submission to the Body Responsible for the OP of all necessary

information regarding the procedures and verifications carried out concerning

operations/projects;

setting up of procedures to ensure the retention of all documents ;

ensuring that all relevant information are available to ensure a sufficiently detailed audit

trail at all times;

appointment of a Risk Manager and Irregularity Officer;

setting up of a risk management reporting system;

setting up of an irregularity reporting system;

setting up internal audit system;

ensuring that information, publicity and visibility requirements are respected;

providing support to the Body Responsible for the Operational programme in the

preparation of the Communication Action Plan for the OP and related activities.

9

10

Figure 3: Institutional / Operating Structure for the Environmental Protection Operational Programme (EPOP)

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

In the context of Priority Axis 1, the EPEEF (as the Implementing Body) is directly responsible

for tendering, contracting and payments at the project level, in accordance with the rules and

procedures of the PRAG, FIDIC, EBRD or other international financial institutions (if

applicable), and national legislation, acting as the Contracting Authority and performing the

following specific tasks:

preparation of procurement plan;

preparation of financial report, including cash flow forecast and submission to the NF and

the Body Responsible for Priority/Measure;

planning co-financing funds in its respective budget/financial plan, if applicable;

preparation of contract forecast, procurement notice, shortlist notice etc.;

preparation of tender documentation and verification of TS/ToRs/Guidelines for

Applicants (the last one if applicable);

submitting of tender documentation to ECD for ex-ante approval;

setting up members of the Evaluation Committee (Shortlist Panel);

chairing Evaluation meetings;

preparation of the Evaluation Report (Shortlist Report) and submitting to the ECD for

approval;

preparing and signing the Contract Dossier/ Addendum Dossier upon ex-ante ECD

approval;

preparing Contract Award Notice;

support to the supervision on technical implementation of project/supervision on technical

implementation of project in case that the Implementing Body is the final beneficiary of

the project;

participating in the Project Steering Committee, if applicable;

carrying out on-the-spot checks at the Contractors/end recipients (at project level);

carrying out verifications to ensure that products or services have been delivered, and

that payment requests/invoices issued by the contractors are correct. These verifications

shall cover administrative, financial, technical (if appropriate, see under l) and material

aspects of operations, if appropriate;

preparing requests for funds and submitting them to the Body Responsible for

Priority/Measure;

executing payments to contractors and recovery of funds to the National Fund, as well as

recovery of unduly used funds;

maintaining a separate accounting system or a separate accounting codification;

ensuring that the Body Responsible for Priority/Measure receives all necessary

information on procedures and verifications carried out in relation to project

implementation and payments;

support to the preparation of documents for Sectoral Monitoring Committee on the

progress achieved in the fulfilment of objectives of the Measure;

support to the preparation of sectoral annual reports and the final report on

implementation;

retaining documents necessary to ensure an adequate audit trail;

ensuring compliance with information, publicity and visibility requirements;

appointing a Risk Manager and Irregularity Officer;

irregularity reporting;

reporting on risk management;

11

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

reporting on internal audit findings;

providing support to the preparation of the Communication Action Plan for the Operational

programme and related activities.

The responsibilities, tasks and relations between the MEPPPC and the EPEEF are regulated

by an official agreement (Operational Agreement for the management and implementation of

the EPOP between bodies of the Operating Structure).

1.5

IPA and the Structural / Cohesion Funds

As envisaged and explained in both of the IPA regulations, a major aim of IPA is to prepare

the beneficiary countries for participation in the Community’s cohesion policy and rural

development instruments after accession to the EU.

The Cohesion Fund (CF) is an instrument aimed at helping EU Member States to reduce

economic and social disparities and to stabilise their economies. It co-finances up to 85% of

eligible expenditure of major projects involving environmental and transport infrastructure.

This helps to strengthen cohesion and solidarity within the EU. Eligibility is restricted to the

less prosperous Member States of the Union whose gross national product (GNP) per capita

is below 90% of the EU-average.

IPA is thus a direct preparation for absorbing those funds which are allocated for eligible

Member States and, since all IPA beneficiary countries are potential members, it is primarily

an instrument directed towards the prospect of EU membership. The rules and procedures for

IPA programming and implementation are similar in most respects to the ways in which EU

funds are managed in the Member States.

A comparison of some of the key features of IPA and the Cohesion Fund is presented in

Table 3. As may be seen, there are very few significant differences and, while there are

some differences applying at the operational level (for example, with regard to eligible costs),

the structures and systems which are being developed for managing and implementing IPA

funds will enable Croatia to access and absorb the much larger funds that will become

available following Croatia's accession to the European Union.

12

8

7

National Strategic Reference Framework (2007-13)

Sector / Regional Operational Programme

7 years; Bulgaria / Romania: 7 Operational Programmes

Maximum co-financing rate: 85% of total eligible project costs

Threshold for Major Projects - €25 for environment / €50M for

transport

Compliance assessment (before intermediate payments)

Decentralised procurement under national public procurement

legislation complying with EU directives

EC Delegation approval not required

Period within which committed funds must be used on programme

level: N+2/3

Eligibility of Expenditures: as defined in Article 3 EC Regulation No.

1084/2006 establishing a Cohesion Fund

Strategic Coherence Framework (2007-13)

Sector / Regional Operational Programme

Initially 3 years; Croatia: 4 Operational Programmes

Maximum co-financing rate: 85% of total eligible project costs 7

Threshold for Major Projects - €10M

Accreditation and conferral (before implementation starts)

Central Procurement

EC Delegation approves all tender documents

Period within which committed funds must be used on programme

level: N+3 8

Eligibility of Expenditures: as defined in Articles 34 and 89 of EC

Regulation No. 718/2007 implementing Council Regulation (EC) No.

1085/2006 establishing an Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance

(IPA)

13

The N+2 (or N+3) rule is a formula applied in the Cohesion Fund, Structural Funds as well as IPA. According to this formula, the funds that are committed in the year "N" must be

used by the end of second (in case of N+2) or third (in case of N+3) year following year "N". In other words, a portion of the budgetary commitment is automatically de-committed by

the European Commission if it has not been used (or if no payment application has been received) by the end of the second (N+2) or third (N+3) year following the year of the

budgetary commitment.

75% for revenue generating investment projects.

Strategic Coordination (Ministry of Finance, PM office, etc)

Structural / Cohesion Funds

Strategic Coordinator obligatory

IPA

Table 3: Comparative Overview of IPA and the Structural / Cohesion Funds

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

2.

PROJECT CYCLE MANAGEMENT (PCM)

The purpose of this chapter is to provide the reader with a basic understanding of:

2.1

¾

Project Cycle Management (PCM), and how PCM should be applied to the development

and implementation of a project.

¾

How the European Commission (and others) use PCM as a framework for project

planning, implementation and evaluation.

¾

The main stages involved in PCM.

¾

Some of the tools that can be used for PCM.

Project Cycle Framework

In 1992, the European Commission adopted Project Cycle Management (PCM), a set of

project design and management tools based on the Logical Framework Approach (LFA),

which was already widely used by many donors, including several Member States, other

international organisations and the UN family, and used or partly used by many partner

organisations of the EC. Different approaches to PCM have been adopted, for example by

the European Investment Bank (EIB), European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(EBRD) and the World Bank. But this chapter focuses on the project cycle framework typically

applied to the development and implementation of environmental investment projects cofinanced by the European Union.

The project cycle represents the critical path for managing projects from conception through

to completion. From the point of view of EU-funded projects, the project cycle comprises

several major phases as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The Project Cycle for EU-Funded Projects

14

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

This cycle is based on the following key principles:

Decision-making criteria and procedures are defined at each phase (including key

information requirements and quality assessment criteria).

The phases in the cycle are progressive – each phase should normally be completed in

order for the next to be tackled with success.

Use of the Logical Framework Approach to analyse problems, and work out a suitable

solution, i.e. project intervention / design (see section 2.2 below).

Production of key documentation in each phase, to ensure structured and well-informed

decision-making (see section 2.3 below).

Consulting and involving key stakeholders as far as possible.

Clearly formulating and focussing on the Project Purpose.

Incorporation at the outset of key quality issues into the project design / definition.

New programming and project identification draws on the results of monitoring and

evaluation of existing projects as part of a structured process of feedback and institutional

learning.

Each phase of the cycle is summarised below:

Programming: Programming refers to the establishment of a general strategy or coordinated

group of activities for providing EU assistance in a country or region. Based on an analysis of

the development context, the problems, needs and opportunities, of other players’ actions and

of national and EU capacities, the focus of EU assistance is agreed with the partner country.

The outcome is an agreed intervention strategy and an internal budget allocation / funding

decision by the European Commission, (e.g. the MIPD and EPOP).

Identification: Identification is the starting point for every individual project and, in the context

of the relevant national strategy and sectoral operational programme, should aim to ensure

that the project meets local / regional needs and is consistent with EC and national priorities 9 .

The main activity during this stage is to define the 'core problem' and its underlying causes

which the project aims to address, and then to generate possible project ideas and

alternatives for solving them. The most important questions that the project developer / End

Recipient should consider at the project identification stage are:

What results do you want to achieve?

How will you achieve these results?

What assumptions are you making?

What are the alternatives?

How much will it cost?

Who will pay for it?

Logical Framework Analysis is a useful technique that can help to answer these questions.

Further information and guidance on project identification and definition is provided in Chapter

4 below.

Formulation: During this stage, a comprehensive project proposal is prepared and a detailed

feasibility study carried out to ensure that the project is feasible and capable of delivering

sustainable benefits. The project developer / End Recipient is mainly responsible for ensuring

that the project proposal is completed properly, and that its main components and

assumptions are adequately analysed and tested for their feasibility. The duration of the

formulation stage may vary greatly for different types of project and will be influenced by the

availability / accessibility of required information, the capacity of key project stakeholders and

the degree of political and administrative support provided by local partners. Large scale,

complex investment projects may take many months or even years to formulate fully. Further

9

The general criteria established for the indicative selection of projects for potential IPA co-financing under Priority

Axis 1 are set out in section 3.1 of the EPOP.

15

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

information and guidance on conducting a feasibility study and preparing a detailed project

proposal is provided in Chapter 5 below.

Implementation: During implementation, the agreed project resources are procured and

used to achieve the project purpose (i.e. the target group(s) receive the planned benefits) and

to support the achievement of the overall policy objectives. The implementation phase of the

project cycle is in many ways the most critical, as it is during this stage that planned benefits

are actually delivered. Progress is monitored and assessed to enable adjustment of the

project to changing circumstances. The Contracting Authority is normally responsible for

project monitoring on the ground (under IPA Priority Axis 1, this is the EPEEF). It is therefore

advisable to consider how a project will be implemented and how monitoring will be

undertaken already during the formulation phase. Further information and guidance on

project procurement, implementation and monitoring is provided in Chapters 6 and 7 below.

Evaluation: The evaluation phase involves a systematic assessment of an on-going or

completed project, its design, implementation and results. The criteria typically applied for

EU-funded projects are:

Relevance: The appropriateness of the project objectives to the problems that it was

supposed to address, and to the physical and policy environment within which it operated.

Efficiency: Whether the project results have been achieved at reasonable cost, i.e. how

well, in terms of quality, quantity and time, the project inputs / means have been

converted into project activities and results.

Effectiveness: An assessment of the contribution made by the results to achievement of

the project purpose, and how assumptions have affected project achievements.

Impact: The effect of the project on its wider environment, and its contribution to the wider

policy or sector objectives.

Sustainability: An assessment of the likelihood of the benefits produced by the project

continuing to flow after external funding has ended (with particular reference to such

factors as ownership of the project by beneficiaries, policy support, economic and

financial factors, socio-cultural aspects, appropriate technology, environmental aspects,

and institutional and management capacity).

These criteria are linked to the Project Logframe (see section 2.2 below). Depending on the

type of project, the evaluation of EU-funded projects is usually undertaken by the responsible

national authorities, the European Commission, or both. However, the Contracting Authority

will be responsible for providing much of the data and information necessary for conducting

project evaluation(s), and should therefore ensure that adequate systems for monitoring and

record-keeping are put in place prior to commencement of the implementation phase.

Audit: During the audit phase, an independent examination and verification of a project is

carried out to ensure that applicable regulations, rules and procedures have been complied

with, and that efficiency, economy and effectiveness criteria are being (or have been) met.

The responsibility for planning, organising and conducting such external audits lies with the

audit bodies of the relevant national authorities and the European Commission.

In practice, the duration and importance of each phase of the cycle will vary for different

projects, depending on their scale and scope and on the specific operating modalities under

which they are set up. For example, a large and complex environmental infrastructure project

may take many years to pass from the identification phase through to the implementation

phase, whereas a project to provide technical assistance may only take a few weeks or

months to commence operations on the ground. Nevertheless, ensuring that adequate time

and sufficient resources are committed in particular to the project identification and

formulation phases is critical to supporting the design, financing and effective implementation

of appropriate and feasible projects.

2.2

PCM and the Logical Framework Approach

The Logical Framework Approach (LFA) is an analytical process and set of tools used to

support project planning and management. LFA is an “aid to thinking”, allowing information to

be analysed and organised in a structured way, so that important questions can be asked,

weaknesses identified and decision-makers can make well-informed decisions.

16

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Over time, different development and funding agencies have modified the formats,

terminology and tools of the LFA. However, the basic analytical principles have remained the

same. The EC has required the use of LFA as part of its Project Cycle Management system

since 1993. Knowledge of the principles of LFA and their application within PCM is therefore

essential for all those involved in the planning, design and delivery of EU-funded projects.

In the context of PCM, LFA is used:

During the identification phase, to help analyse the existing situation, investigate the

relevance of the proposed project and identify potential objectives and strategies;

During the formulation phase, to support the preparation of an appropriate project plan

with clear objectives, measurable results, a risk management strategy and defined levels

of management responsibility;

During project implementation, to provide a key management tool to support contracting,

operational work planning and monitoring; and

During the evaluation and audit phases, to provide a summary record of what was

planned (objectives, indicators and key assumptions), and thus provide a basis for project

performance and impact assessment.

Developing a Logical Framework (or "Logframe") has two main stages, Analysis and

Planning, which are carried out progressively during the Identification and Formulation phases

of the project cycle. These are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4: The Logical Framework Approach

Analysis Phase

Planning Phase

¾

Stakeholder analysis – identifying &

characterising

potential

major

stakeholders; assessing their roles,

capacities and concerns

¾

Developing a Logical Framework

Matrix - defining the project structure

¾

Problem analysis – identifying key

problems, constraints & opportunities;

determining cause & effect relationships

¾

Activity scheduling – determining the

sequence and dependency of activities;

estimating their duration

¾

Objectives analysis – developing

potential solutions for the identified

problems; identifying means-to-end

relationships

¾

Resource scheduling – derived from

the activity schedule

¾

Strategy analysis & development –

identifying and evaluating different

options for achieving the objectives;

developing and selecting the most

appropriate strategy

The principle documented output of the LFA process is a Logical Framework Matrix which

summarises all the key components of a project. The typical structure of a Logframe Matrix is

shown in Table 5.

It should be noted that, while LFA is a valuable tool for project design, implementation and

evaluation, it is not a substitute for other project tools especially those related to technical,

economic, social and environmental analyses. Likewise, LFA does not replace the need for

professional expertise and experience.

The analytical techniques used in the Analysis Phase of LFA are described in Chapter 4

below, while further information and guidance on the Logical Framework Approach is

provided in Annex A.

17

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Table 5: Typical Structure of a Logical Framework Matrix

Project Description

Indicators

Source of Verification

Overall Objective – The

project’s contribution to

policy or programme

objectives (impact)

How will the Overall

Objective be measured

including

Quantity,

Quality, and Time?

How will the information

be collected, when and

by whom?

Purpose – Direct benefits

to the target group(s)

How is the Purpose to

be measured including

Quantity, Quality, and

Time?

As above

If the Purpose is achieved,

what assumptions must

hold true to achieve the

Overall Objective?

Results / Outputs –

Tangible products or

services delivered by the

project

How will the Results be

measured

including

Quantity, Quality, and

Time?

As above

If the Results are achieved,

what assumptions must

hold true to achieve the

Purpose?

Activities – Tasks that

have to be undertaken to

deliver

the

desired

results

2.3

Assumptions

If Activities are completed,

what assumptions must

hold true to deliver the

Results?

Key Documents & Responsibilities

The key documents and primary responsibilities associated with the development and

implementation of waste management infrastructure projects co-financed by IPA under

Priority Axis 1 are summarised in Table 6.

2.4

The Financing Decision

The financing decision represents the legal basis and formal commitment of the EU to finance

a project and / or an agreed programme of measures aimed at addressing identified needs

and solving clearly identified problems. The financing decision for major projects is taken by

the European Commission together with the beneficiary country, while the individual projects

are managed and supervised by the responsible Operating Structure / Sectoral Monitoring

Committee(s). In all cases, project proposals / funding applications are submitted by the

Commission to the IPA Committee 10 for its opinion, before a Commission financing decision

is taken.

Key information required to support a financing decision for a major investment project

includes:

Information on the body to be responsible for project implementation;

Information on the nature of the investment and a description of its financial volume and

location;

Results of project feasibility studies, including the financial analysis;

A timetable for the implementation of the project before closure of the related operational

programme;

An assessment of the overall socio-economic balance of the project, based on a costbenefit analysis, including a risk assessment and an assessment of the expected impact

on the sector concerned;

An analysis of the environmental impact of the project; and

A financing plan, showing and justifying the total financial contributions expected and the

planned contribution from the EU and other sources of financing.

These requirements are described further in the following chapters.

10

The IPA Committee is a committee composed of representatives of the Member States and chaired by a

representative of the European Commission.

18

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

Table 6: Key Documents & Responsibilities – Priority Axis 1 (IPA)

Project Cycle Phase

Key Documents

Primary Responsibility

Programming

Financing Agreement

Environmental Protection Operational

Programme (EPOP)

EC / Government of Croatia

MEPPPC

Identification

EPOP / Identification Fiche

Pre-feasibility Study

ToR for Project Formulation Phase

MEPPPC

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Formulation

Feasibility Study

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Environmental Impact Assessment

Financing Plan

Completed IPA Application Form

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Prospective IPA End Recipient

Procurement Plan

EPEEF

Tender Documents

IPA End Recipient

Tender Dossier

EPEEF

Procurement Procedures

EPEEF

Payment Applications and Orders

EPEEF

Technical Implementation of Service,

Supply & Works Contracts

EPEEF

Contractor's Monthly Report

Contractor

Supervising Engineer's Report

Engineer (FIDIC)

Progress, Financial and Irregularity

Reports

EPEEF

Project Annual Implementation and

Monitoring Reports

EPEEF

Sectoral Implementation Reports

EPOP Operating Structure

Implementation Monitoring Reports

Head of the EPOP Operating

Structure / Sectoral Monitoring

Committee

Evaluation

Evaluation

Interim)

Head of

Structure

Audit

Internal Audit / Irregularity / Risk

Management / Compliance Reports

External Audit Reports

Implementation

Reports

19

(Ex-ante

and

the

EPOP

Operating

Head of the EPOP

Structure

Audit Authority / EC

Operating

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

3.

IPA APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS

The purpose of this chapter is to inform the reader about:

3.1

¾

The process of applying for IPA co-financing of major projects

¾

The general requirements for submitting a major project to the European Commission for

co-financing

¾

The technical, financial, economic, institutional and environmental requirements that must

be met in order to succeed in obtaining EU funding for a major environmental investment

project

¾

The criteria applied specifically to waste management projects

The Application Process

This chapter presents the basic requirements to be met by projects submitted for IPA cofinancing within the framework of the Environmental Protection Operational Programme

(EPOP) 2007 – 2009 for Croatia. Particular attention is given to projects aimed at developing

infrastructure for integrated waste management systems.

The requirements described in this chapter refer only to major projects proposed for cofinancing from IPA. The EPOP (as well as IPA in general) also allows financing of non-major

projects (below 10 million Euro). In line with the IPA implementing regulation, community

assistance is implemented through multi-annual operational programmes. These operational

programmes are drafted by the operating structures. They are finalised in close consultation

with the European Commission and the relevant stakeholders, and approved through a

Commission Decision. According to the IPA implementing regulation, the operational

programme for the regional development component shall contain an indicative list of major

projects, together with their technical and financial characteristics, including expected

financing sources and indicative timetables for their implementation. 11

The indicative list of projects in the water and waste management sectors is included in the

EPOP. The EPOP also presents the key criteria that were applied in drawing up the indicative

list of projects. Inclusion of a project in the indicative list of major projects does not mean that

the project will automatically receive co-financing from IPA resources. The final decision on

project financing is made by the European Commission. All project developers / End

Recipients 12 (i.e. municipal / county / regional companies or other public bodies dealing with

waste management) need to go through the entire application process and ensure the

readiness of the project prior to submitting an application for IPA co-financing.

The application process (for waste management investments) can be divided into the

following stages:

Submission of a detailed feasibility study and an Application Form with all relevant

supporting documentation by the project developer / End Recipient to the Ministry of

Environment Protection, Physical Planning and Construction (MEPPPC). The tasks of the

MEPPPC include inter alia a sound appraisal of major projects prepared by the End

Recipients;

Submission of the project with all the relevant documentation to the European

Commission. If a project is appraised as acceptable, the European Commission will issue

a decision approving each project, which will define the physical infrastructure to be

11

Commission Regulation No 718/2007 of 12 June 2007 implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 1085/2006

establishing an Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA)

12

In previous documents, the term “Final Beneficiaries” was used in place of “End Recipients”.

20

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

procured and the eligible expenditure to which the co-financing rate for the Priority Axis

applies. At the end of the approval process, a Bilateral Project Agreement between the

European Commission and the beneficiary country is signed, confirming these elements.

Complementary funding for the planned investments must be ensured from national

funding, external loans and other sources.

The application process is time-consuming. It takes months (or sometimes more than a year)

before a funding decision is made by the European Commission. Bearing in mind the limited

time frame for project implementation resulting from the de-commitment principle, applicants

should ensure that only well-prepared and supported applications are submitted to the

Commission.

Technical Assistance

Project developers / End Recipients (public administrative bodies) may also apply for

Technical Assistance under the IPA EPOP. This can be used for the preparation of IPA

projects (including preparation of project and tender documentation). It should be noted

that within the budget for IPA project funding, it is possible to earmark financial resources

for day-to-day project management, publicity, etc.

3.2

General Requirements

As stated in the implementing regulation, when submitting a major project to the European

Commission the following information shall be provided:

Information on the body to be responsible for implementation;

Information on the nature of the investment and a description of its financial volume and

location;

Results of feasibility studies;

A timetable for the implementation of the project before the closure of the related

operational programme;

An assessment of the overall socio-economic impact of the operation, based on a cost

benefit analysis and including a risk assessment, and an assessment of the expected

impact on the sector concerned, on the socio-economic situation of the beneficiary

country and, where the operation involves the transfer of activities from a region in a

member state, the socio-economic impact on that region;

An analysis of the environmental impact;

A financing plan, showing the total financial contributions expected and the planned

contribution under the IPA Regulation, as well as other Community and other external

funding. The financing plan shall substantiate the required IPA grant contribution through

a financial viability analysis.

The project developer / End Recipient completes a standard application form 13 in English

and submits all the relevant documents listed in the application form:

Feasibility study (summary and full version);

Cost-benefit analysis;

13

Major Project Request for Confirmation of Assistance Under Article 10 of Regulation (EC) No 1085/2006 and

Articles 157 of the Commission Implementation Regulation No 718/2007. Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance.

Infrastructure Investment. Environment.

21

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

3.3

EIA non-technical summary;

Declaration by the authority responsible for monitoring sites of nature conservation

importance;

Copies of relevant decisions, permits and other documents with English translation; and

Maps of an appropriate scale.

Technical Requirements

The overall objective of the EPOP is to invest in those projects that will deliver the greatest

impact with the limited resources available in the waste and water sub-sectors, whilst

assisting Croatia to meet its obligations for implementation of the EU environmental acquis

governing the treatment and disposal of waste, the supply of drinking water, collection,

treatment and discharge of waste water; and also to develop the administrative and

management capacity of those institutions responsible for implementing the EPOP. 14 Projects

submitted for IPA co-financing must comply with the principles set out in strategic sectoral

documents (such as the National Waste Management Strategy).

The Strategy of Waste Management of Croatia requires that waste management systems be

implemented in harmony with the following principles (a full list of the principles may be found

in the Strategy itself): 15

3.4

Respect for the waste management hierarchy:

¾

The main priority is to avoid and reduce waste generation, and to reduce the harmful

properties of waste.

¾

If the generation of waste cannot be avoided or reduced, the waste should be reused,

recycled and / or recovered.

¾

Waste that cannot be used in a rational way must be disposed of in an

environmentally-friendly manner.

Use of Best Available Techniques (BAT): based on their cost-effectiveness and

environmental acceptability. Emissions from waste treatment facilities and landfill sites,

which are regulated by special provisions, should be reduced as much as practicable,

and in a manner considered to be most efficient from a technical and economic point of

view.

Independence and proximity: An integrated network of facilities and installations for the

recovery, recycling, treatment and disposal of waste, fully compliant with Croatia's

requirements, must be established. In some specific cases, use will also be made of

facilities and installations situated outside of the Republic of Croatia.

Financial and Economic Requirements

IPA applicants are requested to prepare “an assessment of the overall socio-economic

balance of the operation, based on a cost-benefit analysis and including a risk assessment,

and an assessment of the expected impact on the sector concerned, on the socio-economic

situation of the beneficiary country and, where the operation involves the transfer of activities

from a region in a Member State, the socio-economic impact on that region”.

This requirement is met in the form of a Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) for the project,

comprising:

A financial analysis (see section 5.3 of this Manual);

An economic analysis (see section 5.4); and

14

Environmental Operational Programme 2007 – 2009.

2007HR16IPO003. Republic of Croatia; September 2007, p. 52

15

Instrument

for

Pre-Accession

Assistance.

Strategy of Waste Management in the Republic of Croatia; Strategy adopted by the Croatian Parliament on

th

October 14 2005

22

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

A sensitivity and risk analysis (see section 5.5).

This CBA should be conducted in line with the following main EC guidelines:

Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis of Investment Projects - Structural Funds, Cohesion Fund

and Instrument for Pre-Accession; European Commission; Directorate General Regional

Policy; Final Report 16/06/2008 16 ; and

Guidance on the Methodology for Carrying out Cost-Benefit Analysis. Working Document

No. 4; European Commission; Directorate General Regional Policy; August 2006 17 .

The CBA typically forms a significant part of the detailed project feasibility study and must be

attached to the application form (Annex II to the standard IPA application form). The key

findings of the CBA are also reflected in section E of the application form. This section of the

form contains inter alia information on:

Financial Analysis (section E.1 of the application form):

The methodology and specific assumptions applied in the financial analysis (section

E.1.1.);

The main elements and parameters used for the financial analysis, i.e. reference period,

discount rate, investment costs, operating costs, revenues, etc., and the resulting funding

gap (section E.1.2.);

Further main results of the financial analysis (section E.1.3.); and

Revenues generated over the project’s lifetime (section E.1.4.).

Socio-Economic Analysis (section E.2 of the application form):

Description of the methodology used (key assumptions made in valuing costs and

benefits) and the main findings of the socio-economic analysis (section E.2.1.);

Details of the main economic costs and benefits identified in the analysis together with

the values assigned to them (section E.2.2.);

The main input assumptions and outputs of the economic analysis (section E.2.3); and

Employment effects of the project (section E.2.4.).

Risk and Sensitivity Analysis (section E.3 of the application form)

Description of the methodology and summary results (section E.3.1.);

Sensitivity analysis (section E.3.2); and

Risk analysis (section E.3.3.).

Applicants also must present a detailed financing plan for the project. This plan should show

all project-related costs and how these are to be financed. The amount of the IPA grant is

calculated based on the funding gap formula (see section 5.3.6 below). The availability of the

funds to cover the remaining costs (i.e. over and above the IPA grant) must be proven by the

applicant, who must provide "the details of the decision(s) on national public and private

financing, loans, etc." (section D.2.3).

A Financing plan for the project is presented in section H of the application form. All sources

of project co-financing should be reflected in this section. As defined in the National Waste

Management Plan for the Republic of Croatia (2007 – 2015), the Environmental Protection

and Energy Efficiency Fund (EPEEF) plays an important role in co-financing of IPA and (in

future) Cohesion Fund projects. It finances up to 60% of the costs associated with the project

preparation phase (technical documentation, studies etc.). Together with the IPA resources,

the EPEEF finances up to 80% of the eligible construction costs

16

http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/guides/cost/guide2008_en.pdf

17

http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/2007/working/wd4_cost_en.pdf

23

Project Cycle Management – Manual for End Recipients of EU Funds in the Environmental Sector

3.5

Institutional Requirements

One of the key pre-conditions for completing the application process successfully is to ensure

rational and economically viable operation of the resulting infrastructure. Project developers /

End Recipients need to demonstrate that adequate institutional arrangements for the

implementation phase have been developed and agreed. As stated in the EPOP, the criteria

applied during the selection process for IPA co-financed investments include the presence of:

An adequate administrative and institutional framework (this, inter alia, will help to ensure

that the “polluter pays principle” is fully observed); and

A rational and economically viable structure for the future operating company.

The following issues are taken into account when examining project institutional readiness:

Has an institution (such as a county / regional waste management company) already

been established?

Will the infrastructure be managed in a different way after the project is completed (i.e.

public management, new concession, or other form of arrangement)?

What will be the ownership structure of the utility company?

Have municipalities participating in the system signed a formal agreement to deliver

waste to the facilities when they open?

Does the project involve a Public Private Partnership (and if so, what will be the division

of tasks and risks between public and private partners)?

Public Private Partnerships (PPP)

PPPs are a form of cooperation between public authorities and businesses with the aim of

carrying out infrastructure projects or providing services which have traditionally been

provided by the public sector. PPPs typically involve complex legal and financial

arrangements.

Before entering into PPP schemes, public authorities should carefully consider all

arguments for and against this form of service provision. If a decision to proceed with a

PPP approach is taken, particular attention should be paid to the distribution of risk and