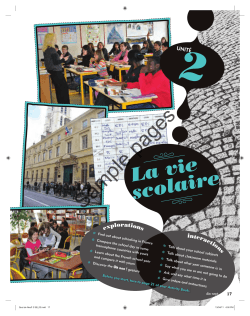

QUID NOVI